The War of 1812

The War of 1812 is considered a major event in Canadian military history. While it concluded with a return of the status quo, the three-year conflict showed that Canadians (i.e., British subjects in Upper and Lower Canada) saw themselves as different from Americans and had no desire to be incorporated into its southern neighbour.

In the opening decades of the 19th century, hostilities between the United States of America (U.S.) and Great Britain had been brewing – namely over maritime commerce and the actions of the Royal Navy. Americans argued that the British were violating shipping laws as well as illegally coercing American sailors to join the Royal Navy. First Nations were another point of contention; Americans were convinced that the British’s sympathy toward First Nations, and the two’s growing positive relationship, would halt American expansion westward into indigenous territory.

On June 18, 1812, U.S. President James Madison declared war on the British Empire. With Great Britain being on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Americans focused on British colonies in Upper and Lower Canada and devised an invasion plan. Madison hoped that by annexing Canada he would secure a more reliable access to the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, thereby facilitating greater control of the exchange of goods to and from Europe. Great Britain was concerned by the declaration of war but was too preoccupied with the Napoleonic Wars raging on the Old Continent to spare any attention or reinforcements for its North American assets. For this reason, Americans assumed the invasion and takeover of Canada would be rapid and easy.

American troops arrived at the border on July 12, 1812, ready to set the invasion scheme into motion. They were, however, unprepared for Major-General Isaac Brock’s bold and spirited response, and their initial invasion attempt failed. The attackers found that the British colonists in Upper Canada were not inclined to American assimilation and thus, were willing to defend their land.

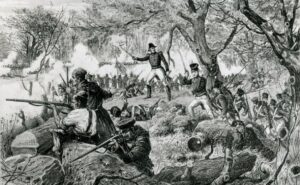

Engraving of the Battle of the Chateauguay. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Fighting occurred in seven theatres of war, four of which stretch along the Canada-US border. The capture of Fort Detroit was the first major British victory. It was followed by the Battle of Queenston Heights (1812), the Battle of Stoney Creek (1812), the Battle of the Châteauguay (1813), and many others. Intertwined with the narrative of the battles are figures such as Brock or Laura Secord whose bravery and fearlessness are engrained in the Canadian collective memory.

At the outset of war, First Nations peoples, led by Tecumseh, forged an alliance with the British who promised them land. For many of the battles, the British found that their support against the Americans proved indispensable.

The Treaty of Ghent, signed in 1815, brought the War of 1812 to an end and reinstated the pre-war status quo. Historians believe the invasion failed mainly because Kingston and Montreal, both very important naval cities at the time, were never captured.

The final three Indigenous veterans of the War of 1812: John Smoke Johnson (left), John Tutela (middle) and Young Warner (left). The picture was taken in 1882 in Brantford, Ontario. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Though British-American relations have been peaceful ever since, both sides were apprehensive in the immediate post-war period and they each prepared for future warfare by increasing fortifications. In Canada, this included construction of the Rideau Canal. It was completed in 1832 and served as an alternative waterway for trade and transportation in the event Americans seized the St. Lawrence River.

One of the lasting outcomes to emerge out of the war was the militia myth – the erroneous belief that Canada could be protected exclusively by its citizens. The reasoning was that since Americans were pushed away largely by Canadian citizens (i.e., British subjects) and First Nations, with only few British regulars alongside, it was thought that the valiant, efficient militia sufficed, and as a result, that a professional army was not useful; this perspective did not change until decades later.

A re-enactment of the Battle of Stoney Creek. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

To continue exploring the War of 1812, see this article by The Canadian Encyclopedia or view the Archives of Ontario’s Digital Exhibit.

Main photo: Brock and Tecumseh look down on Fort Detroit. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Sources:

Benn, Carl. The War of 1812. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2003.

Eustace, Nicole. 1812: War and the Passions of Patriotism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Granatstein, J.L. Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. 2nd ed. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2011.

Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Short History. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Naworynski, PJ, and others, dir. Canada: The Story of Us, episode 3, “War of Independence”. CBC. War of Independence | Canada: The Story of Us, Full Episode 3 – YouTube