Henry’s Sword & The Fenian Raids

Written by Donald V. Macdougall. Don Macdougall is a retired lawyer who enjoys researching the social and employment circumstances of his ancestors. Additional footnotes and details are available upon request: donvmac@gmail.com

This story starts with an old sword in my living room, a medal that was in my father’s sock drawer, and my aunt’s bequest of 160 acres in northern Ontario. The medal’s clasps with the words “Fenian Raid of 1866” and “Fenian Raid of 1870” were the impetus to explore my great-grandfather’s militia service in the Ottawa area from 1861 to 1875.

The Sword, the Medal, and the Land

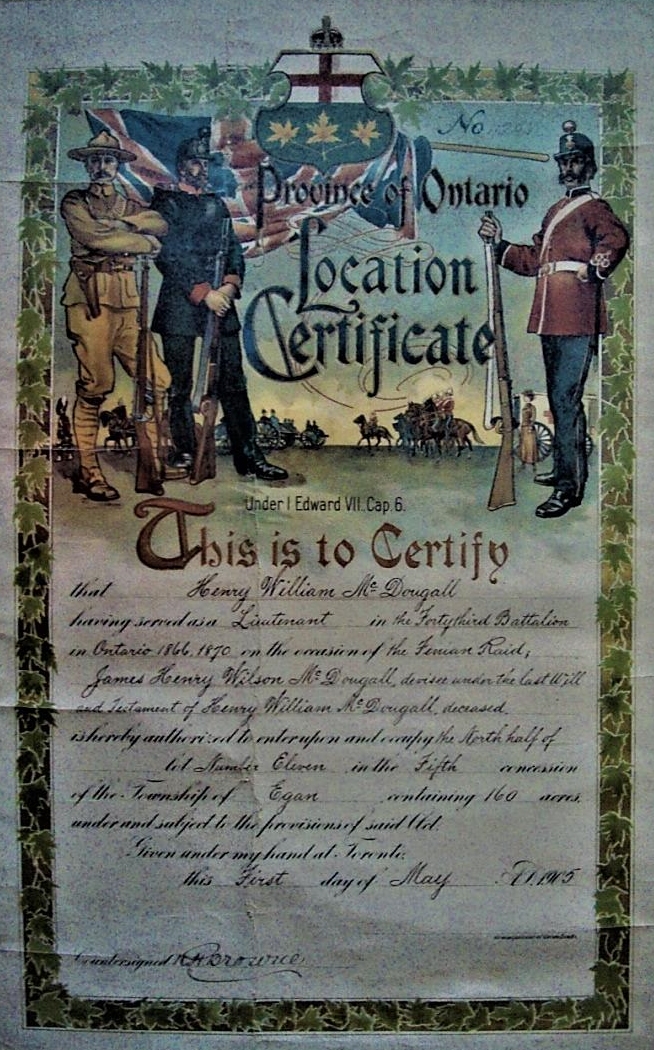

Henry William McDougall kept his sword, and for his militia service during the Fenian raids he was awarded a Canada General Service Medal and granted 160 acres of land in northern Ontario.[i]

The government formally recognized the Fenian raids militia only after a lot of public pressure. In September 1896, Henry was among a large group of “survivors” from the 1866 Fenian raid who met at a public hall in Ottawa and formed the “Veteran Volunteers of ’66 Association of Ottawa” to press for government recognition.

It was almost 30 years after the raids that the Dominion Government in 1899 awarded the Canada General Service Medal to “Canadian forces who had taken part in the suppression of the Fenian raids of 1866 and 1870.” Henry received his medal and two clasps (1866 and 1870) for serving “as guard at a point where an attack from the enemy was expected,”[ii] although there were no actual attacks where he was garrisoned at Fort Wellington, Prescott.

Not only have Henry’s sword and medal been passed down through the family, so has his land grant near Timmins, Ontario.

Henry’s great-great-great-granddaughters wield his sword. (Another of the girls’ 3X-great-grandfathers served with the London Militia in the 1866 Fenian raid and was granted land near New Liskeard.) (Credit: Don Macdougall).

In March 1901, 35 years after the last Fenian raid, Ontario became the first provincial government to recognize and compensate Fenian raid militia with 160-acre grants of Crown land to veterans (or their heirs) who made appropriate applications. It seems, however, that the 1901 “Act to Provide for the Appropriation of Certain Lands for the Volunteers …” was more about efforts to populate northern Ontario than about honouring those who had defended Canada in 1866-1870 (or who had gone to Africa to fight in the Boer War).

Although Henry applied for his grant in 1901,[iii] he died in 1903 before it was awarded; eventually his eldest son obtained the location certificate in 1905.[iv] The land was in “new Ontario”, situated in Treaty 9 land. In 1870, when the last Fenian raid took place, the property was still within Rupert’s Land held by the Hudson’s Bay Company but was purchased that year by Canada after signing the James Bay Treaty (Treaty No. 9).[v]

Location Certificate for the land in Egan Township, an unincorporated northern Ontario township about 52 km east of downtown Timmins (photo by author).

When the patent for the land was eventually issued and registered in 1911, the property was in the District of Nipissing, which later became part of the District of Cochrane. Little Driftwood River (more a creek) cuts through the grant, which consists of forest and swamp, far away from Henry’s last home in Carp, Ontario, and well removed from any inhabitants or road access. It came with mining and mineral rights, but all “pine timber” was reserved to the Crown (valuable to Britain for ships’ masts). Various family members hoped that gold or other valuable minerals would be discovered there, but when the author and his wife hiked in along a logging trail, they found only trees, beaver ponds, mosquitoes, and moose droppings. That undeveloped and still hardly accessible land is now owned by the author, whose current property tax is $50 a year.

Henry and the Voluntary Militia in Canada West

After the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, when war between the United States and Canada seemed inevitable, the “stirring events of 1861” moved “patriots” of Carleton County in Canada West (now Ontario) to organize a group of volunteers who would be ready for active military service when required.[vi] An Ottawa Citizen editorial warned of the “war feeling” between Great Britain and the United States and that “indications are decidedly warlike.”[vii]

The first meeting was held at Bell’s Corners in late 1861 when 55 men established the Bell’s Corners Company.[viii] Henry was appointed a Sergeant, along with J.F. Bearman as Lieutenant, A. Spittal as Ensign, W. Corbett as Color-Sergeant, and R. Spittal and G. Robertson as fellow Sergeants. They all were under Captain W.F. Powell, Carleton County’s Member of the Province of Canada Legislative Assembly (Powell was born in Perth, Ontario, became owner and editor of the Ottawa Citizen and was MPP from 1854 to 1867).

At the time, 20-year-old Henry was an unmarried boot and shoemaker in Bell’s Corners, a “thriving post village of 150 people” in Carleton County about 18 km southwest of Ottawa (now both village and county are part of the City of Ottawa). Since the volunteers had day-time employment, they drilled two or three nights a week. The company was not officially recognized or provided with uniforms and equipment until December 1862 when the Militia Commander in Chief authorized the formation of a “Volunteer Militia Company of Infantry at Bell’s Corners”; this was the nucleus of the 43rd Regiment.[ix] A sergeant was sent as a drill instructor in January 1863, and in February the Agricultural Society and the Militia Company voted to erect a building in Bell’s Corners to be used by the Society as a showroom and as a “drill shed” for the military.

Henry would serve twice on the threatened Canadian border, first in 1865-6 and again in 1870. Both times were at Fort Wellington, protecting Prescott and the route to Ottawa.

The Fenians Wanted to Take Canada

Even before the American Civil War, Irish-American nationalists had formed the Fenian Brotherhood with dreams of attacking Canada. The term Fenian comes from the Irish Gaelic term Fianna Eireann, a band of mythological warriors. After the American Civil War ended in April 1865, the Fenian Brotherhood proposed to mobilize the hardened and unemployed Civil War veterans, seize Canada, and hold it hostage to trade back to Queen Victoria for an independent Ireland.

The Fenian Brotherhood argued that Canadians, especially the Catholic Irish, would welcome them as liberators. A Fenian government for Canada was actually established by the group in New York City, bonds were sold to be repaid by “The Irish Republic,” and military regiments and brigades were formed. “Canada … would serve as an excellent base of operations against the enemy; and its acquisition did not seem too great an undertaking” wrote “General” John O’Neill, the Irish nationalist architect of what are now known as the Fenian Raids.[x]

The 1866 Fenian Scare

On November 15, 1865, the Volunteer Corps in Canada was placed under the command of Lieutenant General Sir John Michael, “commanding Her Majesty’s Forces in North America” and placed on “Frontier Service” with five hundred volunteers stationed in Windsor, Sarnia, Niagara and Prescott.[xi] A contemporary report emphasized the fear and concern in Eastern Ontario:

At … places, such as Cornwall, Prescott, Brockville, Clifton (Suspension Bridge) the local force on several occasions mustered and remained under arms all night to repel anticipated attack, and along the frontier line which extends from Rouse’s Point on the East to St. Regis on the West, great alacrity was manifested, a system of squad alarm posts was established at intervals of two miles along the whole of that line and the spirit and discipline of the Local Force was such as to remove all anxiety for the safety of that, although the most exposed part of the frontier.[xii]

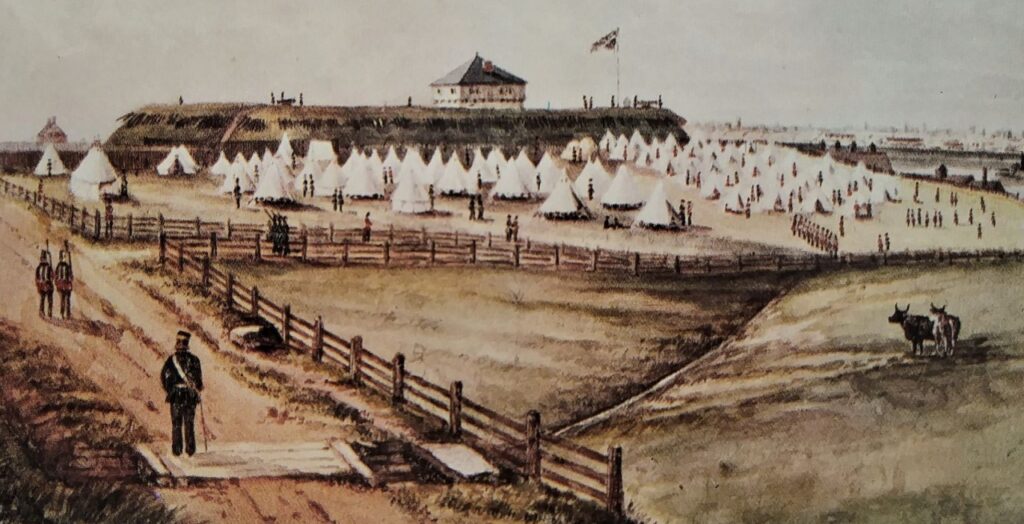

Henry was part of this mobilization, temporarily transferred and stationed from November 1865 through June 1866 on garrison duty as a Cpl (and “Gunner”) in the “Ottawa Garrison Artillery” or “Garrison Battery,” under Cpt AG Forrest on “Frontier Service” at Prescott, camped at Fort Wellington. The militia group travelled by wagons from Bell’s Corners to Ottawa but had to wait there since “the fort at Prescott was not ready for its reception,” then travelled by train about 95 km from Ottawa to Prescott.[xiii] Prescott was a strategic town on the St Lawrence River across from Ogdensburg, New York, at the head of a treacherous 80-km stretch of rapids where goods and troops moving between Montreal and the interior were transferred from bateaux and Durham boats to lake vessels. Fort Wellington had been built there to protect the vessels travelling inland on the river from American attacks during the War of 1812.

Volunteers camped at Fort Wellington during the Fenian Raids (Credit: Fort Wellington National Historic Park, Parks Canada, 1980).

The volunteers joined some Imperial regulars already at the fort and were welcomed:

“Notably from the district behind Prescott and Brockville, on the occasion of an alarm, the country people flocked to those places from considerable distances, each man armed with the best weapon he could pick up.” “The Volunteers who were sent to Prescott, as also the local force called out there, were hailed with great satisfaction by the population of Prescott and of the surrounding country. The reports about the Fenians had produced an alarm all along the frontier.” The commanding officer attributed “our immunity from attack to the fact of there being troops well-armed, well equipped, and now well instructed in gun drill in Fort Wellington.”[xiv]

There were rumours of an imminent invasion by the Fenian Brotherhood for St Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1866, with concentrations of Fenians along the Canadian frontier planning a three-pronged attack at Fort Erie, at Prescott (to seize rail and river communications and march on Ottawa) and through the Eastern Townships. In March 1866, 10,000 Canadian volunteers were called up, and a few days later, when the first session of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada took place in its new capital, Ottawa, the first legislation was to suspend Habeas Corpus, thus denying a court review for arrest.

The “serious threat to the St. Lawrence front was when [the Fenians] massed forces at Ogdensburg for the capture of Prescott. But the presence of a bristling British gunboat patrolling the river and of 2,000 Canadian militia … at their battle stations effectively stopped the intended attack.”[xv]

The first Fenian incursion into Canada, the “raid of ’66” on June 1, 1866, took place near Fort Erie when the Fenians crossed the Niagara River, briefly took Fort Erie, and fought a victorious battle at Ridgeway against Canadian militia (there were no Imperial troops present); they were later forced back across the border. There were nine Canadians killed and 32 wounded. On June 6, American President Andrew Johnson reacted by issuing a “Neutrality Proclamation,” ending Fenian hopes for official support from the American government

Meanwhile in Ottawa

Sandra Gwyn, in her fascinating look at the early days of Ottawa as the capital city, tells us that from the spring of 1866 and especially through the winter of 1869, “Ottawa was a capital in turmoil” as reports of planned invasions dominated other events.[xvi] The new civil servants in Ottawa, even including deputy ministers, were organized into a Civil Service Rifle Regiment (precursor to the Governor-General’s Foot Guards) and required to drill twice a day. Local militia units from the outlying areas began guarding the streets. Rumours included Fenians crossing the ice to Canada from the Ogdensburg area.

While Henry was in Prescott with the Ottawa Garrison Artillery, several militia units including the Bell’s Corners Company were mobilized in March 1866 to be part of a provisional battalion on garrison duty in Ottawa. After performing their first church parade, every man of the Bell’s Corners Company was presented with a bible and prayer-book by Mrs. Powell, wife of the Captain (and later Lt-Col).[xvii] But Cpt Powell himself wrote that Ottawa showed no public appreciation, unlike other parts of the province, even though the volunteers had been called from their homes with an hour’s warning, with no knapsacks provided to carry their clothing, spending six weeks in Ottawa “without a change of boots, socks, flannel shirts, or other necessaries, tramping up and down in wet and slush, night and day….”[xviii] He also noted that “one in every seven out of a Company of strong men” were filling the hospitals because of fever “brought on by wet and exposure.” Another complaint in the Ottawa Times stated that the Township or County council should at least “give the Company a dinner or some demonstrative proof of their patriotism and loyalty.”[xix]

Although the militia men left their employment and rushed to service, some of the political leaders appeared to be less involved. Future Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was serving as minister of militia during the largest raid in 1866. As telegrams poured in with updates about the rebel advances, Macdonald remained far too drunk to read any of them. ‘Hypothesis A would be that he went on a bender from time to time and unluckily the Fenians chose one of those moments to invade,’ historian Ged Martin, author of a 2013 biography of Macdonald, told the National Post in 2015. ‘Hypothesis B would be that he freaked out and took to the bottle.’[xx]

In December 1866, back from the front, Henry was promoted from Sergeant to Lieutenant in Bell’s Corners No. 1 Company (replacing JF Bearman) and received a pay rate of $1.58 for each day’s service.[xxi] A week later on Christmas Eve, he was attending a “grand military ball” in the new town hall at Richmond until four o’clock in the morning along with some officers of No. 5 and No 6 companies and over “one hundred couples” to raise funds for a “drill shed”.[xxii] (Richmond was a village then about 34 km from Ottawa but is now within the City of Ottawa.)

Regulars at Ottawa Firing the ‘ten-des-jours’ on Dominion Day, July 1, 1867, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1867 (Elihu Spencer, print: albumen with hand-painted details) (Credit: Bytown Museum, P2877).

The Birth of a Nation, 1867

On July 1, 1867, Canada’s first Dominion Day, the Bell’s Corners Company were the honour guard at Canada’s first parliament, marching and countermarching on Parliament Hill “under a hot sun”; Lt McDougall earned $1.58 for the day.[xxiii] After parading to City Hall Square, they were told that the City of Ottawa had forgotten to plan food and drink for them, but Alderman John Rochester stepped forward (he happened to be running as a Conservative in the September election) to provide hospitality at “The Grove”, his tavern on Richmond Road, where they marched (as a newspaper reported) “with their tongues hanging out.”[xxiv]

D’Arcy McGee Assassinated, 1868

Fenian alarms declined through 1867, but anxiety rose again in April 1868, when Thomas D’Arcy McGee, “the golden-voiced prophet of Confederation,” Father of Confederation, Member of Parliament, Irish Catholic and vehement objector to the secret paramilitary societies trying to tear down the very country he had just helped to create, was assassinated on Sparks Street in Ottawa. A group of Fenian sympathizers were rounded up and in February 1869, Patrick Whelan was publicly hanged at Ottawa’s Nicholas St Jail for the killing. His last words were “God save Ireland and God save my soul.”[xxv]

Although death masks were a common means of remembering the deceased, McGee had been shot in the head, and this plaster cast of his hand was taken instead, shortly after his death. McGee’s death hand is on display on the third floor of the Bytown Museum. Visitors to Ottawa can also see a glass-enclosed replica at D’Arcy McGee’s, an Irish pub about a block from the assassination site.

The voluntary militia continued to prepare. Target practice, using the “valuable” Enfield Rifle distributed to the volunteers, was “considered as the most important branch of the instruction of the Volunteer,” resulting in rifle matches throughout the province (one match lasted 10 days).[xxvi] As well as active service, Henry participated in many rifle shooting matches between the companies and won a number of prizes.

All companies of the 43rd Carleton Battalion assembled together for the first time in June 1868 for an encampment in Sandy Hill, Ottawa (on the “elevated plateau which lies between the Government Rifle Range and Daly Street, on the bank of the Rideau”).[xxvii] The Bell’s Corners No. 1 Company comprised 52 men under Cpt Corbett and Lt HW McDougall. The company had to provide the tents and all necessary camp equipment themselves.[xxviii] They were described as a “very fine body of men,” who “improved during the time they were together, but require a great deal of drill to make them steady under arms.”[xxix] When they mustered by wagon for the annual drill a year later, in October 1869 (receiving rations of 25 cents a day while at the camp), the inspectors made the same assessment.[xxx]

The 1870 Fenian Panic

The second time Henry was sent to the front was for garrison duty at Prescott in 1870, as Lieutenant in the Ottawa Provisional Battalion & Independent Companies under Lt Col J Bearman.[xxxi]

In May 1870, Fenians crossed the border into Quebec from near Franklin, Vermont, but were quickly forced back. Reports from government detectives in the United States had raised alarms of an impending invasion; the 43rd was ordered from Ottawa at midnight on May 25, 1870, arriving in Prescott some six hours later. Henry was there with Bell’s Corners Company No. 1, from May 26 to June 4 (and earned $23 in total).[xxxii]

Map of eastern Canada West showing Ottawa, Richmond, Prescott, and Ogdensburg (Credit: 1864 Mitchell map of Ontario).

Fenians collected for several days across the St Lawrence at Ogdensburg and along the river, but steamer patrol on the river seemed to deter them. Accompanied by field artillery, about three hundred Canadian militiamen performed sentry duty, conducted patrols, and stood guard duty at the local drill shed, artillery stables, local bank, town wharf, Fort Wellington and Windmill Point but returned to Ottawa in June after the threat had passed without incident.

Effect of the Fenian Raids

Even considering Fenian invasions in 1866 and 1870, D’Arcy McGee’s 1868 assassination and a terrorist sabotage of the Welland Canal in 1869, some historians have categorized the Fenian Raids period largely as “a comic-opera adventure” that united the three original colonial partners of Confederation, improved the amateur defenders and also persuaded the British to remove their garrison, which some had viewed as a costly provocation for North American conflict.[xxxiii] During the Civil War, British concerns about American expansion had receded, but the Irish nationalist raids by the Fenians into Canada strengthened the belief that Britain’s imperial position needed British North American unity.[xxxiv] The Fenian threats had exacerbated anxiety about American expansionism and were one factor in the push for Confederation.

Social relations were also affected, at least for the short run. Some Irish Catholics left Canada for the United States, and the Orange Order (Protestant and loyal to Britain) acquired bragging rights as national defenders.[xxxv] When Ontario’s Attorney General proposed to release the few Fenian prisoners, public outcry dissuaded him.[xxxvi]

Henry and the 43rd Battalion after the Fenian Raids

One official record shows Henry as “acting” Captain, replacing Cpt Thomas Good, of No. 5 Company, Richmond (where Henry’s brother and a number of relatives lived) for eight days in 1870/ 1871.[xxxvii] He may have left Bell’s Corners as a result of the extensive Great Fire of August 1870 that devastated much of Carleton County, including Bell’s Corners.

On December 3, 1875, the “43rd ‘Carleton’ Battalion of Infantry” was “disorganized” and “removed from the list of corps of Active Militia,” although some of the companies were “detached from the Battalion and made independent companies.”[xxxviii] Henry himself was “removed from the list of officers of the Active Militia.”

One commentator later noted that “the greatest asset of the militia was its zeal.”[xxxix] During his military career in the militia, Henry seemed an eager participant but was spared any direct combat – there was no Fenian blood on his sword.

Henry Carries On

Henry’s early life had been eventful. Young Henry had grown up in rural Montreal Island until he was orphaned at age five in 1846 when his father drowned (his mother had died a year and a half earlier). He was taken in by his maternal uncle Joseph Brown (and family with six children), a tavern keeper and grocer in Montreal. Henry’s four siblings were scattered, two brothers Duncan and Joseph were sent to maternal family members farming in Goulbourn Township (near Richmond), his sister Elizabeth went into domestic service in Montreal, and his eldest brother John started work in Montreal. According to family lore, Henry left his uncle’s family in Montreal at about age 12 and joined a circus. When the circus came to Richmond, he was discovered by another of his maternal uncles and joined brothers Duncan and Joseph at the Brown family farm. That farm was a War of 1812 military land grant to Henry’s great uncle Thomas Brown, when his British 100th Regiment of Foot or “Prince Regent’s County of Dublin Regiment” (renamed 99th in 1816) was disbanded in 1818 after Canadian service in the War of 1812.

In 1874, Henry (1841-1903) married Zebba Margaret Wilson Bangs (1849-1935), worked for a while as a carriage maker in Richmond with his brother Duncan and then was a carriage maker, court clerk, census taker and postmaster in Carp, Ontario, where he lived the rest of his life with his wife and children. As census taker, Henry signed his name “McDougall”, but after his death, it appears that his family adopted the spelling “Macdougall”. Zebba’s father, independent fur trader James Smith Bangs, featured in a previous Families article.[xl]

Henry’s wife Zebba, front row right, with her daughter Agnes Gertrude Macdougall (second row right) and son James Harry Wilson Macdougall, top and other relatives (Credit: I. Acheson collection).

Henry’s descendants are now scattered throughout North America and the UK.

Addendum: Researching the Militia

Using my great-grandfather Henry as the central research character, I often found the proliferation of volunteer militia units confusing. There are numerous documents, but as the colony of Canada (Canada East and Canada West) transformed into part of the Dominion of Canada, militia units were frequently reorganized and renamed.

The militia began in 1793 when all able-bodied men between 16 and 50 years of age (except for religious pacifists and some public officials) were required to enrol, and those reporting for militia duty were listed on muster rolls. Units were organized on a county basis and required to serve in case of war; they gathered annually on the King’s birthday for basic training.

By the mid-1800s, Britain’s policy was to spend less on colonial defence and capital development. Many of the British Imperial regiments had withdrawn from the Canadian colonies leaving only a few militia units as defenders in the event of an invasion across the border. In November 1838, the British authorities had to quickly gather local militia when American and Canadian rebels invaded a few kilometres downriver from Prescott in what became known as the four-day violent and bloody Battle of the Windmill.

In 1855, the previous system of mandatory militia enrolment was replaced in Canada West by an active voluntary militia. In 1859, the Union Government of Canada East and Canada West reorganized the many divergent independent militia companies into Battalions, and by 1863 there were 22 restructured Battalions. Henry’s 43rd Battalion was composed of a number of companies in its military district.

The militia was comprised primarily of small, independent companies scattered throughout the province, but in October 1866 it was officially announced that the new “43rd ‘Carleton Battalion of Infantry’” (headquartered at Bell’s Corners) would, as a Battalion in the “Provisional Brigade of Garrison Artillery” (headquartered in Prescott), combine six volunteer militia companies that had been organized in Carleton County. The Bell’s Corner Company became “No. 1 Company, Infantry Company, Bell’s Corners,” under Cpt W Corbett.[xli] The 43rd was later recognized as “one of the finest units in the Canadian Militia at the time of Confederation.”[xlii] After Confederation in 1867, the federal Militia Act (1868) divided the whole country into nine military districts, each with further reorganizations.

During the Henry’s involvement from 1861 to 1875, the militia units were restructured and renamed from time to time, but the individual volunteers’ duties and conditions remained basically the same. Obligations were not onerous, mostly involving participation in periodic drilling exercises, camp excursions and social gatherings.

While the 43rd Battalion officially terminated in 1875, and although there is some controversy about the strict “lineage” of the 1866-1875 Battalion, in 1881 six companies were designated in a somewhat differently organized way as the “43rd Battalion of Ottawa and Carleton Rifles,” later becoming a regiment called the 43rd Regiment Ottawa and Carleton Rifles, then the 43rd Regiment Duke of Cornwall’s Own Rifles (plus, according to one history, the 207th Ottawa-Carleton Overseas Battalion during WWI[xliii]), and eventually the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa.[xliv]

Main photo: Don’s great-grandfather Henry in militia uniform holding his sword (Credit: I. Acheson collection) flanked by Henry’s Canada General Service Medal; his name, rank and unit are engraved on the medal’s rim (Credit: Don Macdougall).

Inset photo 1: Henry’s great-great-great-granddaughters wield his sword. (Another of the girls’ 3X-great-grandfathers served with the London Militia in the 1866 Fenian raid and was granted land near New Liskeard.) (Credit: Don Macdougall).

Inset 2: Location Certificate for the land in Egan Township, an unincorporated northern Ontario township about 52 km east of downtown Timmins (Credit: Don Macdougall).

Inset 3: Volunteers camped at Fort Wellington during the Fenian Raids (Credit: Fort Wellington National Historic Park, Parks Canada, 1980).

Inset 4: Regulars at Ottawa Firing the ‘ten-des-jours’ on Dominion Day, July 1, 1867, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1867 (Elihu Spencer, print: albumen with hand-painted details) (Credit: Bytown Museum, P2877).

Inset 5: Thomas D’Arcy McGee, 1868 (Credit: Historical Society of Ottawa).

Inset 6: Darcy McGee’s death hand (Credit: Bytown Museum).

Inset 7: Map of eastern Canada West showing Ottawa, Richmond, Prescott, and Ogdensburg (Credit: 1864 Mitchell map of Ontario).

Inset 8: A modern map shows the route from Ottawa to Prescott/ Ogdensburg (Credit: Government of Ontario).

Inset 9: Henry’s wife Zebba, front row right, with her daughter Agnes Gertrude Macdougall (second row right) and son James Harry Wilson Macdougall, top and other relatives (Credit: I. Acheson collection).

References:

[i] The sword blade is embossed with designs, “Canada Artillery”, and “Firman & Sons 153 Strand London”.

[ii] Canada General Service Medal Register, 1866-1870, p. 96, p. 136, Library and Archives Canada.

[iii] Henry W McDougall’s Application for Grant of Land (Oct. 8, 1901), which appears to be in Henry’s own handwriting, Archives of Ontario.

[iv] Henry’s son, Harry, was also a member of the militia and notably at about age 19 served as a private attending the Great Fire of April 1900 that destroyed much of Hull, Quebec, and a large portion of Ottawa: Pay-List of 43rd Ottawa-Carleton Rifles 26 April 1900.

[v] The James Bay Treaty (Treaty No. 9) was entered into in 1905-1906 with adhesions to the Treaty made in 1908 and 1929-1930 and is an agreement between the Crown (represented by two commissioners appointed by Canada and one commissioner appointed by Ontario) and Ojibway (Anishinaabe), Cree (including the Omushkegowuk) and other Indigenous Nations (Algonquin): “The James Bay Treaty (Treaty No. 9)”, Archives of Ontario.

[vi] (a) The “Trent Affair” threatened war between the United States and the United Kingdom when, during the American Civil War, the U.S. Navy captured a British Royal Mail steamer with two Confederate envoys onboard, dispatched by Confederate President Jefferson Davis to secure British and French recognition of the Confederate States of America. (b) “Military Organization,” Ottawa Citizen, December 20, 1861. (c) “Interesting Historical Sketch of Inception and Progress of Forty Third Rifles’ Regiment,” The Saturday Evening Citizen, October 26, 1912, p. 14.

[vii] Ottawa Citizen, December 20, 1861.

[viii] EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), p. 20.

[ix] (a) “Militia General Order No. 2, 5 December 1862”, The Canada Gazette, No. 49, Vol XXI (December 6, 1862), p 3289. (b) EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), p. 20. (c) H & O Walker, Carleton Saga (1968), p. 32-35.

[x] T Hopper, “The time Irish armies kept invading Canada”, Montreal Gazette, March 17, 2021.

[xi] (a) “Military General Order No. 1 of 15 November 1865”, Volunteer and Service Militia List, 1st Mar 1866, p. 63. (b) Report of the State of the Militia of the Province of Canada, 1866, p. 2.

[xii] Report of the State of the Militia of the Province of Canada, 1866, p. 2.

[xiii] “The Frontier Men,” The Ottawa Citizen, November 17, 1865, p. 2.

[xiv] (a) Report of the State of the Militia of the Province of Canada, 1866, p. 7. (b) “Report by Lt Col Atcherley (Prescott),” 1865-66 State of the Militia of the Province of Canada (May 1866), p. 34.

[xv] H & O Walker, Carleton Saga (1968), p. 35.

[xvi] S Gwyn: The Private Capital (1984), p. 99.

[xvii] (a) “Interesting Historical Sketch of Inception and Progress of Forty Third Rifles’ Regiment,” The Saturday Evening Citizen, October 26, 1912, p. 14. (b) EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), p. 24.

[xviii] “Correspondence. Volunteer Relief Fund”, The Ottawa Times, May 29, 1866.

[xix] “Local News”, The Ottawa Times, April 14, 1866.

[xx] T Hopper, “The time Irish armies kept invading Canada”, Montreal Gazette, March 17, 2021.

[xxi] (a) “Militia General Order No. 4, 14 December 1866”, The Canada Gazette, No. 50, Vol XXV (December 15, 1866), p 4813. (b) The Annual Volunteer and Service Militia List of Canada, 1st March, 1867 (1867), p. 129. (c) “Militia General Orders”, The Ottawa Times, December 17, 1866, p. 2.

[xxii] “Military Ball in the Village of Richmond”, The Ottawa Times, December 27, 1866.

[xxiii] “Weekly Drills, No. 21, Cpt Corbett No. 1 Co Bell’s Corners”, Canada, Nominal Rolls and Paylists for the Volunteer Militia, 1867, 43rd Regiment.

[xxiv] H & O Walker, Carleton Saga (1968), p. 356.

[xxv] S Gwyn: The Private Capital (1984), p. 57, 100, 109, 112.

[xxvi] Report of the State of the Militia of the Province, 1863 (1864), p. 16, 19.

[xxvii] (a) The Volunteer Review and Military and Navel Gazette, June 29, 1868. (b) Report on the State of the Militia 1868, p. 42. (b) “The Carleton Volunteers”, Ottawa Citizen, July 3, 1868 (which provides a detailed description of the camp). (c) 1869 Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada (No. 10), p. 42.

[xxviii] (a) EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), p. 28. (b) 1869 Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada (No. 10), p. 42.

[xxix] 1869 Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada (No. 10), p. 42.

[xxx] Report on the State of the Militia 1869 (October 1869), p. 76.

[xxxi] (a) Canada General Service Medal Register, 1866-1890, p. 89, Library and Archives Canada. (b) Henry W McDougall’s Application for Grant of Land, 1901, Archives of Ontario.

[xxxii] Pay List of Company No. 1 Bells Corners of the Forty Third Battalion Volunteer Militia for the period May 26th to June 4, 1870.

[xxxiii] (a) CP Stacey, Canada and the British Army, 1846-1871: A Study in the Practice of Responsible Government (1963). (b) D Morton, How has Canada Responded to Serious Threats in the Past? CIAJ Conference on Terrorism, Law & Democracy; How is Canada Changing Following September 11 (2002).

[xxxiv] J Phillips, P Girard, RB Brown, A History of Law in Canada (2022), p. 27.

[xxxv] D Morton, How has Canada Responded to Serious Threats in the Past? CIAJ Conference on Terrorism, Law & Democracy; How is Canada Changing Following September 11 (2002).

[xxxvi] (a) H Senior, The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raiders, 1866-1870 (1991). (b) D Morton, How has Canada Responded to Serious Threats in the Past? CIAJ Conference on Terrorism, Law & Democracy; How is Canada Changing Following September 11 (2002).

[xxxvii] (a) Acquittance Roll of the No. 5 Co 43rd Batt of Active Militia for Drill Pay for the year ending 30 June 1871. (b) In the 1871 Census, Henry was listed as a 28-year-old carriage maker, in Richmond with his brother Duncan (a blacksmith) and Duncan’s family.

[xxxviii] “Militia General Order No. 2, 3 December 1862”, The Canada Gazette, No. 23, Vol IX (December 4, 1875), p. 694.

[xxxix] H Senior: The Last Invasion of Canada the Fenian Raids, 1866-1870 (1991), p. 188.

[xl] Donald V. Macdougall, “He Drowned With His Money Belt On,” Families (November 2019), p. 3.

[xli] (a) “Militia General Order No. 6, 5 October 1866”, The Canada Gazette, No. 40, Vol XXV (October 6, 1866), p. 3756. (b) EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), p. 24.

[xlii] H & O Walker, Carleton Saga (1968), p. 32-35.

[xliii] “The Carleton Blazers”, The Whiz Bang (Ottawa), July 15, 1916, p. 1-2.

[xliv] (a) The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/military-history/history-heritage/official-military-history-lineages/lineages/infantry-regiments/cameron-highlanders-of-ottawa.html (accessed January 2023)). (b) EJ Chambers, A Regimental History of the Forty-Third Regiment, Active Militia of Canada (1903), chapter V. (c) “Interesting Historical Sketch of Inception and Progress of Forty Third Rifles’ Regiment”, The Saturday Evening Citizen, October 26, 1912, p. 14. (d) “Ottawa Valley Sprang to Defence When a Fenian Raid Threat”, The Evening Citizen (Ottawa), October 10, 1931. (e) C Scott, The Canadian Army in Ottawa, Historical Society of Ottawa.