Frank Wong

Chinese people have faced significant discrimination, prejudice, and racism for much of Canada’s history. The Second World War presented the Chinese community with a unique opportunity to prove their loyalty and patriotism to Canada, and to strengthen their argument for full and equal rights as Canadian citizens. Many Chinese people living in Canada at the time, particularly those who were born in Canada, were eager to enlist when war broke out. As Frank Wong put it:

“I felt it was my responsibility [to enlist] and I figured if I join the army there’s a possibility that after the war, I may be able to get the franchise. And, to prove to the government my loyalty to my country”

Born May 16, 1919, in Vancouver, BC, Wong was not considered a Canadian at birth due to discriminatory laws of the time. Indeed, Wong’s early life would be tainted by ever-present racism. In an interview with Senior Living Magazine in November 2010, Wong recalled:

“I was born in Canada and was proud to be Canadian, but there was so much discrimination. We were not allowed to go in a public swimming pool and if we went to the movies, we had to sit in the back row.”

These may have seemed trivial at the time, but it is important to remember that these “small” acts of discrimination served as constant reminders that the Chinese were second class citizens in Canada.

Wong was 22 years old when the Canadian government removed restrictions barring Chinese Canadians from service and he enlisted soon after. Wong was posted with the Royal Canadian Ordinance Corps of the First Canadian Army. He completed his basic training in Vernon, BC, and trade-specific training in two Ontario cities, Barrie and Ottawa. For Wong, the military was one of the first places he felt truly treated as an equal by other Canadians:

“As far as I was concerned, the military was very good to me, I felt confident. For the first time in my life, I felt that I’m somebody, I’m a regular Canadian citizen, and [there was] no discrimination. I was very happy. I remember when I was in the service, I used to get a lot of invitations into people’s home for dinner, and everything. Hard to believe, here I was Chinese, and I’m supposed to be inferior to the Caucasian, and everything, and yet, I’m invited, I’m in Ottawa, I was invited to their home for Christmas dinners. They say, “You live too far away, well come and join us for Christmas.”

After completing their training in Canada, Wong’s unit would be stationed in England for the next year and a half. His unit was a second echelon mobile workshop tasked with maintaining and repairing the guns of the Royal Canadian Artillery, which meant the unit was under constant threat of enemy fire due to their proximity to the front. A month after D-Day, Wong deployed into Normandy, France. The first thing he is told when he lands on Juno Beach? Keep moving! Don’t linger because the beach was still under enemy fire. At that point in the war German forces were still close enough to strike the beach with long range artillery pieces and they conducted nightly air raids at the beachhead – hoping to destroy critical infrastructure, supply lines and support units.

Wong would be promoted to Corporal shortly after landing in Normandy, a total shock as he assumed his ethnicity would have held him back:

“Being the only Chinese […] I was surprised when, after we landed in Normandy, on Juno Beach, that they – I think a week, or ten days after that, they made me a corporal. And I said, “Wow, I’m surprised,” I said, “I’m the only Chinese!” And yet, I was made a corporal. So, I have no problem with my unit, the people respect me.”

Wong and his unit would follow the First Canadian Army through Normandy. By the time Wong’s unit neared the front, most of the German Army was in complete retreat. He remembers this period of the war as an exhilarating time. Whenever they neared a village, people would come to greet them bearing gifts of flowers, wine, and pastries. Once the Canadian Army pushed through to Holland there was a dramatic shift in tone. The longer the war dragged on the worse conditions in occupied countries became. The Nazi war machine demanded higher and higher contributions from occupied territories, leading to acute food and fuel shortages. By the time the First Canadian Army was liberating the Netherlands in late 1944, the Dutch were starving. Wong recalls the experience in an interview for the Memory Project:

“It’s kind of sad, you know. I remember, in Holland, we first moved in there, the people were starving. And I do remember some young kids, we would put some of the garbage in the garbage can, they were fighting all over the garbage. So naturally, we’d eat half of our meal, and then we gave the other half to the kids. And then when our officer found out what we were doing, then he put the guards around the whole – like our kitchen – and prevent these kids from coming into our line to pick up, because they said, “You need the food.” We say, “We have the organization that’s bringing in the food to defeat the civilian [hunger].” They say, “You need all the food.”

Following the Nazi surrender, Wong would not immediately return to Canada. His unit was tasked with clearing Arnhem, a city in the Netherlands, of booby-traps so it was safe for civilians to reinhabit the city. They lost another six soldiers clearing the mines, an emotional blow to the unit that hit especially hard given the war had ended. Despite his service and newfound respect, he would still not be recognized as a Canadian until 1947 when Chinese Canadians were finally granted full rights as Canadian citizens.

Wong was a founding member of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum, located in Vancouver. On May 8, 2003, Wong was presented with the Kingdom of the Netherlands Medal of Remembrance for his part in the liberation of Holland. Wong returned to the Netherlands and Normandy several times, participating in various remembrance ceremonies. As a visiting Canadian veteran, Wong would often be asked for his autograph following Dutch ceremonies. At one ceremony, Wong had a book with him which he asked a few of the kids to sign in return for his autograph. He would remember the phrase one of the kids wrote for the rest of his life, a phrase he believed perfectly captured the Dutch attitude towards Canadians:

“Your blood, our freedom”

Frank Wong died on September 12, 2013, at the age of 94.

Additional Information & Further Reading:

The Louie Brothers – Two Chinese Canadian brothers who served in WW1, despite being exempt from conscription at the time due to racist governmental policies.

Peggy Lee – A Chinese Canadian women who served in an all-Chinese St John’s Ambulance Corps unit during the Second World War.

Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society (CCMMS) – An organization that aims to “collect, preserve, document and commemorate the role of Chinese Canadians in service to Canada’s military with a focus on the role these “unwanted soldiers” played in the community’s efforts to achieve full equal rights in Canada.”

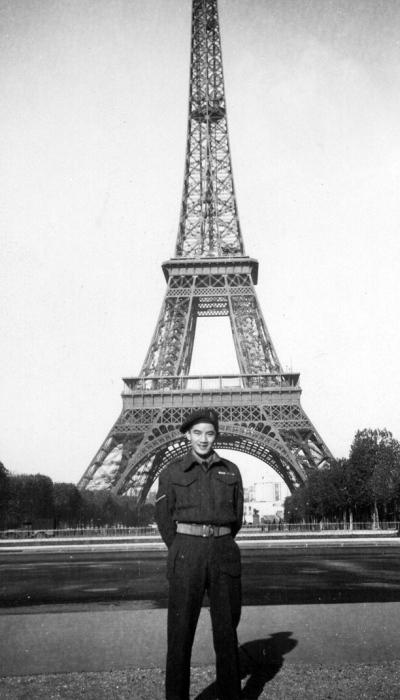

Main: Wong (front) with friends, Belgium, 1944. (Credit: The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society)

Sources:

CBC News. 2008. “Chinese-Canadians remember wartime dream of equality in Vancouver.” Accessed August 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/chinese-canadians-remember-wartime-dream-of-equality-in-vancouver-1.763331.

The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society. n.d. “Frank Wong.” Veteran Stories. Accessed August 2023. https://www.ccmms.ca/veteran-stories/army/frank-wong/.

The Memory Project. n.d. “Frank Bing Wong.” Historica Canada. Accessed August 2023. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/mpsb-frank-bing-wong-primary-source.

Thomas, Mia. 2003. “Frank Wong: Honoured for his contributions.” Burnaby Now, June 4. Accessed August 2023. https://www.ccmms.ca/veteran-stories/army/frank-wong/frank-wong-honoured-for-his-contributions/.

Wong, Frank, interview by Ramona Mar. n.d. Heroes Remember – Canadian Chinese Veterans Accessed August 2023. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/chinese-canadian-veterans/profile/wongf.