Trenches and Tunnels at Vimy Ridge

Among the many tunes to have echoed amidst the shellfire and chaos of the First World War, “My Little Wet Home in the Trench” was one of the most appreciated by soldiers. This is unsurprising, seeing as WW1 and trenches are inseparable ideas. In the face of unceasing machine gun and shredding artillery fire, troops had no choice but to dig in and keep their heads down. They lived in de facto ditches that inevitably collected water during any precipitation event and the resulting conditions made their time there, in most cases, quite unpleasant.

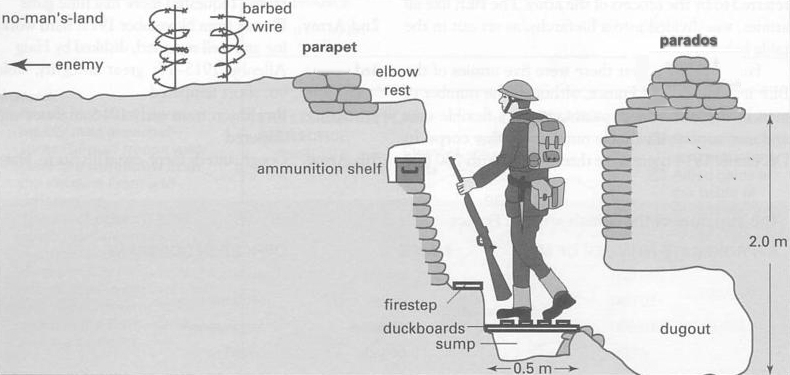

Trenches were limited to a depth of 1.8 meters (or six feet), perhaps a little less if in soggy terrain, and muddy walls were reinforced with wood or corrugated iron. Although trenches gave rise to multiple problems, complex and sophisticated mazes of trenches materialized on the Western Front as the gridlock of the war became increasingly obvious.

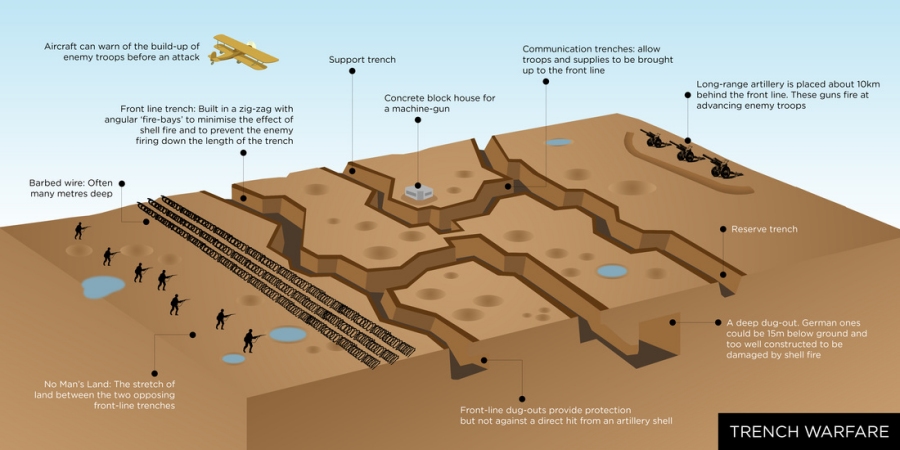

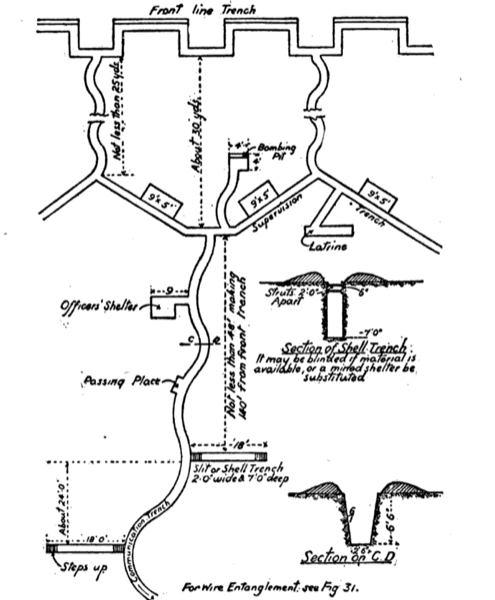

Trenches were categorized into three main categories: front lines, support lines, and reserve lines. Within the front lines, the fire line was closest to the enemy, overlooked no man’s land and housed most of the machine guns (some were also scattered in well-hidden areas further back). To prevent a direct line of fire in case enemies penetrated the trenches or a shell exploded within, the front-line trenches featured a zigzag pattern and were never perfectly straight. Fire bays, straight trench sections that were integrated every 30 to 40 meters and arranged parallel to the enemy’s position, were used for rifle firing by units of soldiers. Close behind, but very well connected to the fire line, was the command or supervision trench. Then came the support lines – ideally 65 to 90 meters from the front lines. Troops stationed there were meant to serve as reinforcements or to enable counterattacks against the enemy. Finally, 370 to 550 meters away, were located the reserve lines.

Also, communication lines intersected trenches at regular intervals and allowed for supplies and men to move back and forth between the three lines. These were critical passageways and were frequently targeted by the enemy.

For added protection against lethal enemy fire, sandbags were packed along the edge of the trench facing the enemy to form the “parapet”. Soldiers were tasked with maintaining these sandbags which required continual replacement because of rot, movement, and a drop in the bag’s density (i.e., leaking from gun and shell shrapnel). With the extra 0.5 – 1 meter parapet built upon the trench’s front wall, soldiers could fire over it with greater ease and limit the risk of being spotted. Parados, known as the higher-than-parapet rear wall of the trench, provided a covering backdrop that prevented the heads of exposed soldiers appearing easily to the enemy against the horizon line.

A diagram of an idealized version of front-line trenches, showing the fire line and the supervision line. (Credit: Notes for Infantry Officers on Trench Warfare)

By the fall of 1915, dugouts became increasingly common in the communication and support lines as soldiers understood that they were about to spend another rough winter in the trenches. Dugouts were small, subterranean rooms accessible from the main trenches via stairs. They afforded more protection from enemy fire and the elements, though the cleanest and most comfortable dugouts were reserved for officers. Some other soldiers would use funk holes, a very small hollowed out area in the trench wall that if used in concert with a tarp, offered some protection from the elements.

For the average soldier, life in trenches was rudimentary and uncomfortable. Stale water pooled and feet got wet causing men to suffer from “trench foot”, an infection which in the worst-case scenario led to gangrene and amputation. Rats, lice, and illness were also rampant. Proper sanitation conditions were very difficult to uphold.

With such time and energy invested in creating these elaborate webs of trenches taken along with the fact that exploding artillery shells were by far the largest killer of WW1, battlefield positioning was largely static and the observed fighting practices reflect that. “The aim of trench fighting is, therefore, to create a favorable situation for field operations” as explained in a British manual for officers.

Trench raiding, the act of small groups of soldiers who perform surprise attacks on the enemy’s trench positions, was invented by Canadian soldiers, and took place regularly. These attacks were rapid, often occurred under the cover of darkness and kept the opponent apprehensive and uneasy. They commonly resulted in enemy positions being purposely damaged as prisoners or valuable information were collected.

The Tunnels

Prior to the Canadian Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917, both the British and the French had put sizeable effort into carving trenches and tunnels into the underlying chalk bedrock. The Canadians, who arrived in late 1916, were no different. Because German troops had elevation in their favour (they were perched atop the ridge and could easily monitor the actions of their opposition), further development of Vimy’s trenches and tunnels was the answer to keeping a low-profile while hiding and protecting thousands of men and tons material. As clearly put by Gordon Thomas, “this time we weren’t digging trenches, but chalk tunnels and we lived in caves in the side of the ridge.” Countless men, mules and horse were utilized to help further build and expand the tunnels, some of which were first excavated hundreds of years earlier during medieval times.

The network of eleven tunnels – for a combined length of six kilometers – was the optimal hiding location of troops, supplies, and artillery. There was even a telephone line running through the tunnels which eliminated the need for hundreds of men to painstakingly re-bury cable once the ground had been overturned by enemy shelling. Most tunnels were less than 500 meters, but others like the Goodman tunnel some 8 meters underground, stretched to 1,600 meters. A marveled Sam Sharpe wrote to his sister that it was “the most wonderful dugouts and tunnels you ever saw all over here […]. There is room here for a small tramway and it is entirely electrically lighted. We are certainly having some experience.” The tunnels contained offices, living quarters and even medical aid stations. Some even had reservoirs of fresh drinking water for soldiers and work horses.

Members of the 22nd Infantry Battalion tried to clear the water from the trenches, circa 1916. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Beyond the engineering feat, the tunnels were also strategically important for the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Smaller tunnels called “saps” were carved near German tunnels and trenches as to listen-in on the enemy. In some cases, explosives were strategically planted and then detonated to annihilate the enemy’s network of tunnels. This helped weaken Germans before the attack. During the lead-up, and on the day of the battle, Canadian troops were hidden in the tunnels, enabling them to by-pass the deadly no man’s land and arrive directly at German lines. Because Canadians were so well concealed, Germans underestimated their numbers, and the element of surprise was amplified.

Today, the trenches of Vimy Ridge have been brought back to life with concrete sandbags so visitors can amble in the footsteps of soldiers and experience trenches first-handedly. Three of the tunnels (Cavalier, Goodman and Grange) are within the bounds of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial and the latter tunnel is open to visitors.

More information:

If you wish to find out more about trenches, including those at Vimy Ridge, or what daily life was like at Vimy, visit Valour Canada’s Road to Vimy Ridge.

To experience a virtual tour of the trenches at Vimy Ridge, see the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, courtesy of Google Streetview.

For a real tour of the tunnels, The Durand Group may be able to help.

Main photo: Visitors can explore the preserved WW1 trenches at Vimy Ridge. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Sources:

Cook, Tim. At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the Great War 1914-1916. Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2009.

Cook, Tim. Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War 1917-1918. Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2008.

Foot, Richard. “Battle of Vimy Ridge.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Last modified on April 6, 2017. Battle of Vimy Ridge | The Canadian Encyclopedia

Granatstein, J.L, Canada’s Army, Waging War and Keeping the Peace, 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Great Britain War Office. Notes for Infantry Officers on Trench Warfare. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1917.

Library and Archives Canada. “The Battle of Vimy Ridge.” Last modified on March 17, 2017. The Battle of Vimy Ridge – Library and Archives Canada (bac-lac.gc.ca)

Mansbridge, Peter. “Exploring Goodman Subway.” CBC News: The National. November 10, 2014. YouTube video, 7:55. Exploring Goodman Subway – YouTube