The Nile Voyageurs

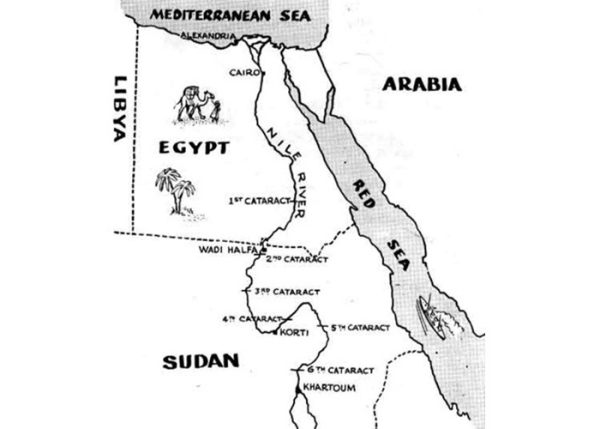

A 2,000-kilometer trip upstream, 6 long rapids, and a grueling and punishing sun; these were just some of the near insurmountable challenges faced by the 400 Canadian voyageurs of Canada’s first contingent to serve overseas as they swerved around the twists and bends of the Nile River.

The year 1884 ushered in a period of great instability for northeastern Africa. The British-supported Egyptian Khedive, feeling threatened by the ambitious Sudanese Mahdi, agreed to retreat from Sudan with the assistance of British forces led by Major-General Charles Gordon. Before all Egyptians could safely be evacuated out of the city of Khartoum in Sudan, Gordon and his men were trapped and besieged. In response to the outcry of public support, the British government agreed for General Sir Garnet Wolseley to lead a rescue party up the Nile to Khartoum.

Earlier, during the Red River Resistance of 1870 (also known as the Red River Rebellion), the immense skill and competency displayed by voyageurs had impressed Wolseley who solicited their aid to help his soldiers navigate the temperamental waters of the Nile. He submitted a request to the Canadian government and within one month a contingent of 400 Alexandria-bound men sailed from Montreal. The men departed on Sept. 14, 1884 and arrived in Egypt less than a month later (7Oct).

Though the group presented a variety of ages, ethnic backgrounds and languages spoken, most worked in lumber and were familiar with waterways. Among them was Chief William Prince of the Manitoba Ojibwa, the ancestor of renowned WW2 and Korean War veteran Tommy Prince.

A map of Egypt and Sudan indicating the six challenging cataracts (or rapids) faced by the voyageurs. (Credit: Canada’s History)

As Wolseley anticipated, Canadians proved agile at maneuvering small boats along the large river. In fact, they were considerably more efficient and effective than their British counterparts. Canadians once again earned the praise of Wolseley who later wrote that “their skills in the management of boats in difficult and dangerous waters was of utmost use to us in our long ascent of the Nile. Men and officers showed a high military and patriotic spirit.” For weeks on end, they tirelessly worked their way up the longest river in the world. Six men rowed each boat guided by one voyageur, either at the helm or the bow.

Yet, Wolseley and the rest of the expedition were pressed for time if they wanted to save Gordon – still sieged in Khartoum. To hasten the trip and further familiarize themselves with the river, the voyageurs broke into groups with each group posted along a specific section of the river. However, that and a short-cut across the Sahara Desert was not sufficient and Khartoum was taken by the Mahdi.

British General Sir Garnet Wolseley sought the help of Canadians to assist his soldiers and officers up the Nile. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

By then, the voyageurs’ 6-month contracts had expired and most opted to return in time for the spring logging season. The need for their expertise was also reduced for the return trip as they now sailed downstream. In all, sixteen Canadians perished during the expedition, mostly due to drowning or disease. Though they never saw combat and failed to reach their objective in time, the operation was a success with Canada’s first overseas contingent igniting the pride and imagination of Canadians. They had shown to the British Empire that Canada was a valuable member and capable of rising to the occasion when called to assist.

For a more in-depth exploration of the expedition, see Legion Magazine’s Voyageurs On The Nile.

Main photo: A gathering of the Canadian voyageurs in Ottawa near the Canadian Parliament. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Sources:

Benn, Carl. Mohawks on the Nile: Natives Among the Canadian Voyageurs in Egypt, 1884-1885. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2009.

Boileau, John. “Voyageurs On The Nile.” Legion Magazine, January 1, 2004.

Historical Society of Ottawa. “The Nile Voyageurs, 13 September 1884.” Accessed on July 21, 2021. The Nile Voyageurs – The Historical Society of Ottawa (historicalsocietyottawa.ca)