In March of 1942, Prime Minister William Mackenzie King declared that “Officers of the Canadian naval service have expressed the view that within a few months submarines may well be found operating within the gulf, and even in the St. Lawrence River.” King’s words would ring true indeed. As predicted, German U-boats had reached Canadian waters by May, bringing the reality of the Second World War closer to Canada than it had ever been.

Over the next five months, from May to October 1942, over 70,000 tons of shipments would be swallowed by the waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence courtesy of German U-boats. The first attack came during the night of May 11 when an unidentified U-boat torpedoed SS Nicoya, a carrier of war material, that was just 600 kilometers north-east of Quebec City. Within a few hours, SS Leto was also sunk, leaving a combined total of eighteen people dead.

At the time, the most important Canadian shipping port was Montreal, meaning all vessels and convoys followed a predictable route along the St. Lawrence River and through the Gulf. U-boats took advantage of this pattern and, to boost their effectiveness even further, U-boat “wolfpacks” would prey on convoys before they reached deep waters. The results were Allied ships going down one after the other, with U-517 responsible for the majority of the casualties.

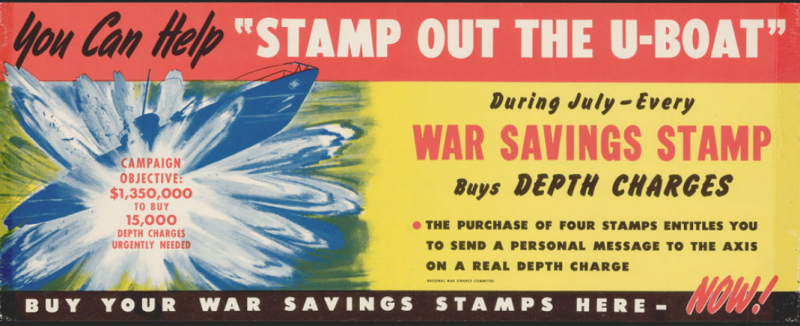

A wartime poster encouraging Canadians to buy war stamps to defeat U-boats. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

For the first time, war did not seem as distant to Canadians. The Nazi threat was real and at their doorstep. Canadians, and Quebeckers particularly, worried that Canada was not adequately protected.

The continual attacks weakened morale within the Allied shipping lanes despite the Royal Canadian Navy’s (R.C.N.) attempts to protect convoys as much as possible. The Royal Canadian Air Force’s depth charges did not suffice to halt the U-boats either. The latter’s presence in the Gulf resulted in a drop of 25 percent in shipments which in turn reduced the quantity of war supplies reaching Europe. Following a series of attacks in early September (including the sinking of HMCS Raccoon), the waterway was temporarily closed to trans-Atlantic shipping.

The 1942 campaign culminated with the sinking of SS Caribou, a civilian ferry connecting Sydney, Nova Scotia, to Port aux Basques, Quebec. The minesweeper accompanying the ferry, HMCS Grandmère, caught sight of U-69 just as it torpedoed Caribou on October 14. Within three minutes, the ship disappeared below the water line in the dark, night sky. Women and 11 children figured among the 137 lost by that attack.

Pictured here is U-190. It was one of the many German U-boats swarming the Gulf of St. Lawrence. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

The five U-boats still swarming in the area left thereafter, bringing the 1942 season to an end, but not the Battle of the St. Lawrence. German submarines eventually returned and continued to take lives. The final major episode of the battle was the sinking of HMCS Shawinigan in 1944 and its 91 dead – the most considerable loss of life experienced by the R.C.N.

For more details concerning the Battle of the St. Lawrence and the various U-boats and warships involved.

Main photo: U-889 as it surrenders to the R.C.N. in 1945. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Sources:

Government of Canada. “The threat from within: SS Caribou sunk during Battle of the St. Lawrence 78 years ago.” Last modified January 26, 2021. Navy News | The threat from within: SS Caribou sunk during Battle of the St. Lawrence (forces.gc.ca)

Iarocci, Andrew and Jeffrey Keshen. A Nation in Conflict: Canada and the Two World Wars. Edited by Colin Coates. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

McNaught, Jack. “The Battle of the St. Lawrence.” Maclean’s Magazine, November 1, 1949.

Veterans Affairs Canada. “The Battle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.” Remembrance Series, 2005.