The Battle of Cut Knife Hill (1885)

During the 1870s and 1880s, relations between the Canadian government and Indigenous Peoples deteriorated and became increasingly strained. First Nations faced unkept treaty promises and were weakened by a dwindling bison population upon which they depended for food. The Métis, feeling neglected and ignored by the federal government, sought recognition for land titles. Many communities began to resist within this context and in response thousands of Canadian soldiers and militia men were swiftly dispatched to the prairies in 1885 by the Canadian government.

Under the authority of Lieutenant-Colonel (LCol) William Otter, a portion of the men trekked through the prairies up to Fort Battleford, Saskatchewan, with the intention of protecting the fort and local white settlers from Cree or Assiniboine attacks. Otter’s men included members of the North-West Mounted Police, the Queen’s Own Rifles, and the Battleford Rifle Company (later the 16th Mounted Rifles).

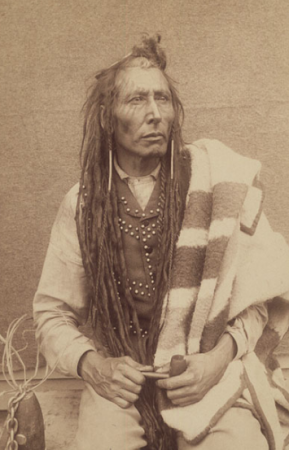

Unease set in when the Cree Poundmaker Band and the Assiniboine – on the verge of famine – came to the fort seeking food rations. Fearing conflict and violence, particularly as the some of the Assiniboine had recently murdered two white settlers, locals found protection within the palisade of Fort Battleford. Yet, Chief Poundmaker thought it more productive for First Nations to collaborate and negotiate with the Crown, rather than forcefully work against it. He hoped that by peacefully speaking to the Indian Agent he would be able to convince the government to honour their treaty obligations. The Chief was unsuccessful and some in his party looted a few abandoned homes in desperation as they left and headed west.

LCol Otter arrived at the fort shortly thereafter and, disregarding orders from General Middleton to leave First Nations people alone, he and his troops quickly departed and travelled 60 kilometres in search of the Poundmaker Band.

The next morning, on May 2, 1885, LCol Otter and his men attacked the Poundmaker Band camp. The First Nations and Métis peoples, headed by Chief Fine Day, defended themselves and confrontation ensued in the grasslands and ravines of Cut Knife Hill. As it turned out, LCol Otter was ill-equipped to face his opponents who were well-versed warriors and familiar with the terrain. Otter’s two cannons were purposeless once their rotted carts disintegrated, and his Gatling gun was unable to fire far enough to reach the opposition. As a result, the LCol’s forces were driven to leave the battlefield, marking the final defeat of Canadian forces during the 1885 North-West Resistance (also known as the North-West Rebellion). Although some Indigenous warriors were inclined to pursue Otter’s retreating force, Poundmaker discouraged further violence. The 6-hour clash left 17 men wounded and cost the lives of another 14, eight from the militia and four Cree.

The North-West Resistance was quelled within a couple of months and its participants were prosecuted for their involvement. Poundmaker was deemed liable for generating the Battle of Cut Knife Hill and declared a traitor. He was briefly imprisoned before his death the following year at Blackfoot Crossing, Alberta. In 2019, he was fully exonerated by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. “Chief Poundmaker was peacemaker who never stopped fighting for peace. […] [He was] someone who work[ed] tirelessly to ensure the survival of his people and hold the Crown accountable to its obligations as laid out in Treaty 6,” he declared.

Poundmaker is now recognized for his peacemaking efforts and has been absolved of all treason charges. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

The battlefield was proclaimed a national historic site in 1923.

For a more complete summary of the 1885 North-West Resistance, see the Canadian Encyclopedia.

Peter Decoteau of the Red Pheasant Cree Nation partook in the battle. Read this article to learn about the accomplishments of Peter’s son, Alex.

Main Photo: An artistic rendition of the Battle of Cut Knife. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Sources:

Chaput, John. “Cut Knife Hill, Battle of.” In Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia, edited by University of Saskatchewan Press. Cut Knife Hill, Battle of – Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia – University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

Government of Canada. “Fort Battleford National Historic Site.” Last modified March 8, 2018. History – Fort Battleford National Historic Site (pc.gc.ca)

Granatstein, J.L, Canada’s Army, Waging War and Keeping the Peace, 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Taylor, Stephanie. “Justin Trudeau exonerates Saskatchewan chief of historic treason conviction.” Global News, July 8, 2019.