No. 2 Construction Battalion

Courtesy of Mathias Joost, CD

At the start of the First World War tens of thousands of men rushed to recruiting centres across Canada to enlist. Black-Canadians were among them. While 70 were able to enlist, 24 of them would later be released, most of them because of the colour of their skin. In addition, to the end of 1915 about 200 Black men were turned away at recruiting centres.

Some Black community leaders wrote to their member of parliament, to the Governor-General or to the Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes about these rejections. Senior militia officers were also concerned as they too were aware of the situation; however, they would not interfere with a battalion commander’s choice to pick and choose the people in his unit. Black leaders and members of the militia began to call for a segregated Black unit. Sam Hughes even stated that a Black unit would be formed, but later went back on his word.

In finding a solution to the problem of Black recruitment, Canada had to consider the policies of the British government and military, as the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) operated under their command structure. The problem with an all-Black combat unit was that the British would never allow it to serve on the Western Front. Further, it was already apparent that the high casualty rate of troops at the front meant that there were not enough Black men in Canada to support an infantry battalion. Major-General Willoughby Gwatkin, head of the militia, came up with the solution. He proposed forming a Black labour unit. The prime minister approved this, as did the British.

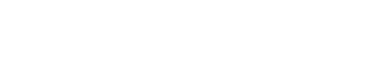

A copy of the recruitment poster for the No. 2 Construction Battalion currently hanging at the Halifax Citadel National Historic Site (Credit: Meghan Groff/HalifaxToday.ca).

No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized on 5 July 1916. It was allowed to recruit across Canada, starting first in Nova Scotia and by September in Quebec, Ontario and the western provinces. Although the battalion had an authorized strength of 1,049 officers and soldiers, recruiting was never able to reach this number. Many Black men had already joined combat units while others refused to enlist, likely disillusioned by previous rejections. When the battalion left Halifax for Liverpool, England, on 28 March 1917, it only had 595 soldiers. Many of those left behind were ill, while many of the others had been rejected as physically unfit for military service.

Once in England, the question became what to do with an under-strength battalion. The British would not allow it to proceed to France in this state. The solution was to reorganize the battalion as a labour company of 500 men, renamed No. 2 Canadian Construction Company. As to where to employ them, the Canadian Forestry Corps (CFC) needed labourers to support its operations. For the CFC this was a bonus as labour battalions were in very high demand.

No. 2 Construction Company arrived in the Jura District of southeastern France on 21 May. Here they were to support the local CFC companies in their operations. Working around the area of La Joux station, east of Champagnole, the company helped cut trees, move them to the mills and then cut them into finished lumber. They then transported the lumber to La Joux station and loaded them by hand onto railway cars. In some instances, this was a 24-hour a day operation. There was more to their service, however. The company helped build and then operate a logging railway. They operated the water system that pumped water to all of the camps, and later operated and maintained the electrical system. They also improved and maintained the logging roads through the forest.

Two detachments from the company would be created, one of 50 personnel sent to support No. 37 Company, CFC in northeast France and another of 180 to support the CFC companies of No. 1 District west of Paris. The latter were sent to this area in the mistaken belief that the men from the southern United States and Caribbean would not be able to handle the winter in the Jura area. In Jura, the battalion had its own small medical clinic and could use the services of the larger Canadian hospital at Champagnole. To get them through the winter they had wooden huts, heated by wood-fired stoves.

Canadian Forestry Corps, Timber Yard, France c. 1918 (Credit: Canada DND/ LAC M# 3523256).

Although many of the Black soldiers of No. 2 Construction Company would liked to have fought the Germans, the closest they ever came to doing so was in April 1918 when they began training in infantry skills in case they were needed to turn back the German spring offensive. They were never used in that capacity. Instead, they continued to provide vital support to the logging operations, which provided boards for trenches and observation posts, boards for walkways, and starting in April 1918, spruce lumber for the French aircraft industry. All of this lumber was in high demand and helped protect the troops from German fire.

With the services they provided, No. 2 Construction Company allowed the CFC logging companies to concentrate on cutting and milling. Each mill was therefore able to produce an average of about 45,000 foot board measure (FBM) of timber a day, compared to about 20,000 FBM for companies that did not have this support.

The armistice of 11 November 1918 signalled the end of combat for the First World War. As a result, lumber was no longer required, and therefore, the services of No. 2 Construction Company ended. In mid-December the three elements of No. 2 Construction Battalion were reunited in England to begin their preparations for a return to Canada. As the men from the battalion were recruited from across Canada, they returned on multiple passenger ships on different days starting in January 1919.

No. 2 Construction Battalion remains the largest segregated unit in the history of Canada. As with 75 percent of the CEF, they never saw combat. However, their services were vital to the men in the trenches. Despite the problems that were initially there, the men of No. 2 Construction Battalion represented their communities with honour. This effort was not without its cost. Between 28 December 1916 and 29 May 1919, twenty-nine of the Battalion’s men died, mostly from diseases and illnesses.

To learn more, review Library and Archives Canada’s: War Diaries – 2nd Canadian Construction Company.

Main photo: Members of No. 2 Construction Battalion. (Credit: Halifax Herald, July 6, 2016).

Our thank you to Mathias Joost, CD, for allowing us to post this article.