Major Jack Cade

Researched and written by Jenny Cade. Minor edits by Valour Canada.

The Korean War did not end in 1953, it froze. The Korean Armistice Agreement halted open hostilities, but left the peninsula divided, tense, and bristling with uncertainty. For the men and women tasked with maintaining the fragile ceasefire, the conflict lived on in patrols, negotiations, and division. Among them, was Major Jack Cade of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) regiment.

Preamble

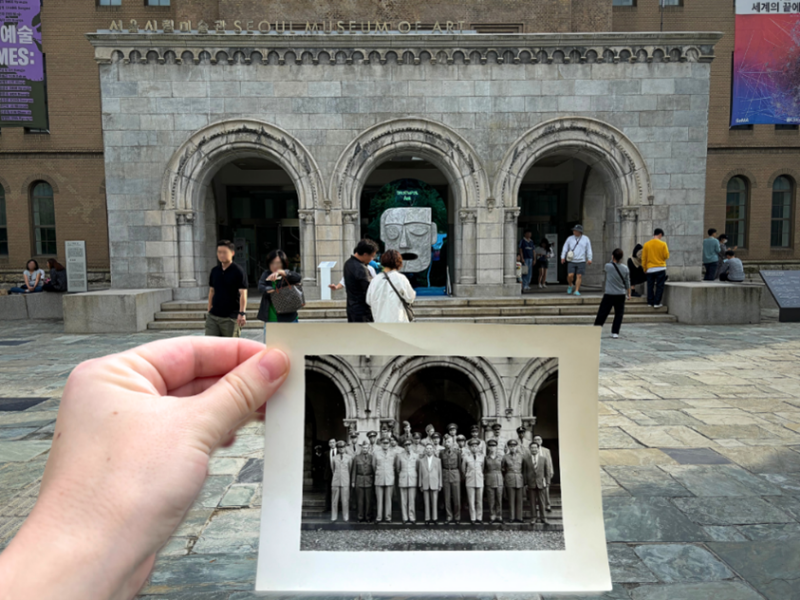

From 1959-1960, my grandfather, Major Jack Cade (Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) – LdSH), served as a part of the Joint Observer Team (JOT) in Korea, which is known today as the Special Investigations Team of United Nations Command (UNC) Military Armistice Commission. I lived in Korea for 3 years (in part) due to how positively he spoke of Korea and its people. So, when I found photos of my grandfather in Korea, it was a collision of lived worlds and I sought to retrace some of his steps. What follows are stories he’s told, his work with UNC, and what his “footsteps” look like today. In short, this is a glimpse into one LdSH mission through a modern ‘lens’.

The Mission after the Korean War

While negotiations for peace between North and South Korea first began in 1951, a peace treaty was never signed. In lieu, an Armistice Agreement was signed in 1953 to cease military hostilities. The agreement established a ceasefire, a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea, and an agreement that each side would have a JOT (comprised of 4-6 officers) to assist the Military Armistice Commission in ensuring that the Armistice Agreement was upheld. UNC would go on to appoint a team representing South Korea in 1959, which had Maj Jack Cade representing Canada, along with representation from other nations.

The Helicopter Incident

As part of their work, the JOT needed to view and assess defences against North Korea. But Korea’s mountainous terrain can make travel challenging, thus air logistical support would sometimes be required. However, helicopters weren’t always reliable either, which Maj Cade became acutely aware of when his team’s helicopter to scout ROK 3rd Division’s territory stopped functioning in mid-air:

“We had been flying north for 1 hour and had just crossed a range peak and started down towards the valley below; we were about 3500 feet up. Suddenly there was dead silence except for the breathing of the members aboard. “Tighten seatbelts, relax and lean forward,” crackled the intercom. “There is a clearing directly below where I intend to set down.” The intercom snapped off, the only sound being the rush of wind through the blades, then a bone-jarring jolt, a slight bounce, and the aircraft was on the ground. At this point we realized that we were still in a very precarious position. The helicopter hit the ground on the side of a mountain about 2800 feet from the valley floor. The only thing preventing the aircraft from falling was the rotor blade sticking in the ground; would it hold or break? No one knew! As soon as the rear door was open the pilot instructed the person closest to the door to move out. After the third person had left, the remainder were told to hold fast. The co-pilots then left the aircraft with a rope and tackle and with the assistance of the others, secured the aircraft to a tree stump a few yards away.”

JSA & Encounters with the North

The Joint Security Area (JSA), located within the DMZ, served as the primary venue for diplomatic meetings between North Korea and UNC. These talks addressed issues such as alleged armistice violations, troop movements, and general security concerns.

When I lived in Korea (2009-2012), South Korean nationals and foreigners were able to visit the JSA, but today it remains closed to public access. Luckily with support from UNC’s Public Affairs team, I was able to capture these moments in history as they appear today.

Maj Cade’s duties also extended beyond the JSA and into actual North Korean territory. In one story, the JOT headed north to address a formal complaint:

“The escort was made up of South Korean soldiers armed with automatic rifles, submachine guns, and grenades. Most were of the 16- to 18-year-old variety with no battle experience and extremely nervous. I am sure a wrong move upon contact with the North Koreans would result in a shootout. The group, led by the soldiers, moved along a single-foot path until we reached the barb wire fence. We now found ourselves in the middle of “No Man’s Land” unable to move forward without the consent of the other party. Suddenly a loud crashing noise drew our attention north; at the same time approximately 15 North Korean soldiers arose from hidden positions on their side of the barb wire and leveled loaded rifles at us. All noise stopped; after about 5 minutes their leader emerged and exchanged credentials. We then proceeded through the wire into North Korea.”

After a three-mile trek to meet with North Korean and Chinese representatives, the team was presented with the remains of a soldier and accusations of espionage. However, upon closer inspection, it was revealed that the supposed “spy” was carrying U.S. identification papers made of rice paper and wore boots with soles and heels crafted from Chinese materials. The JOT declared “non-acceptance” of their case, sparking a tense three-hour debate over whether the person was truly a spy. Finally, it was decided to refer the allegation to the Full Military Commission for resolution, and the team made a (hasty) return south.

The April Revolution

Maj Cade’s role also included meeting prominent political figures and being a ‘literal’ witness to major historical events unfolding in this newly formed republic [South Korea]. The April Revolution in 1960 was an uprising led by university students against South Korea’s first president, Syngman Rhee. So, when the JOT heard that “all hell had broken loose in the capital,” they quickly jumped in a U.S.-marked car and headed to Seoul to observe and assess.

“Arriving at the Chosun Hotel, we moved down main street towards the government buildings. Suddenly, “ping, ping, ping,” resounded through the whole car, immediately followed by the “ta, ta, ta, ta,” chatter of a machine gun. The driver veered to the side of the curb and cut the motor; at about the same time the three of us, exiting the car, hit the side of the walk. Suddenly a rush of air followed quickly by a large orange flash as the front windows disintegrated into the street. The students had thrown a firebomb into the [police station]. Smoke poured into the street followed by policemen frantically trying to get out of the burning building. Our car had sustained about dozen bullet holes but was in running order. After a quick conference and the sound of approaching sirens, we decided to get the hell out.”

The JOT escaped the area and — after a tense exchange with a police barricade — made their way to the Foreign Officer Compound where they learned of the April Revolution and the actions taking place across the city. The next day they learned that Lieutenant-General Yo Chan Song had moved the ROK 3rd Division into Seoul and declared Martial Law. President Rhee was forced to resign and go into exile in Hawaii.

Denouement & a Thank You

In 1960, my grandfather’s time in East Asia came to an end. While he rarely spoke about his experiences during WWII, he was always open and positive when sharing stories of his time in Korea. His love for the country ultimately inspired me to pursue this project. Although I never had the chance to tell him how deeply his stories influenced me — or that some of the places he visited are now just a subway ride away — I felt it was important to honour his legacy by sharing this history with the people he cherished most, the Strathconas.

Great things are never accomplished alone. I want to extend my heartfelt gratitude to LCol John Kim (Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians)) for his invaluable support and for opening my eyes to how much further this project could go. A special thank you to the UNC Public Affairs team for their contagious passion and assistance, and to my considerate friend Alex Moon for connecting me with the War Memorial of Korea. I am also deeply appreciative of Jeongyeop Kim from the Curatorial Department for their help in identifying key locations, and to Col (ret’d) Spike Hazleton (Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians)) for sparking this initiative. Finally, my deepest thanks go to my husband, my biggest cheerleader, for his constant encouragement and support.

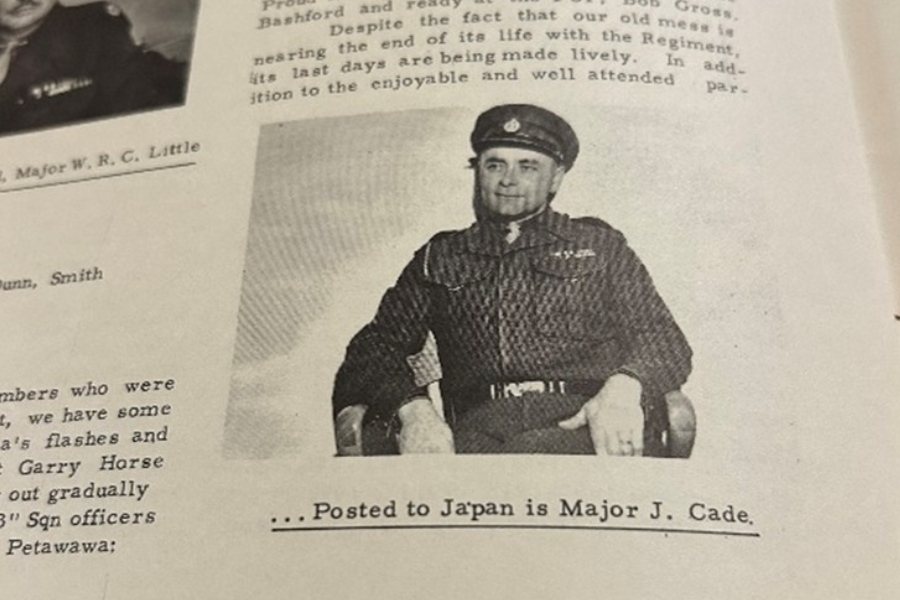

Main photo: The Strathconian announces Major Jack Cade’s posting to Korea-a posting which includes the territory of Japan where UNC Headquarters was once based. (Credit: Jenny Cade)