Election of 1917: Military Service Act

When Canadians went to the polls on December 17, 1917, they realized that their votes could potentially affect the outcome of the First World War. If they supported Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Unionist¹ government they would be voting in favour of the Military Service Act, young men would be conscripted for service, and many would be sent overseas to fight. If Canadians instead voted for Laurier’s Liberals, the Canadian Corps would be less able to help Britain and our allies win the war, however, many young men could remain at home in Canada.

¹ The “Unionist” government consisted of MP’s who supported conscription. They were a collection of conservatives, independents, and like-minded liberals who disagreed with Laurier and Bourassa.

Soldiers of the Canadian Corps casting their ballots at the Western Front in December 1917 (Credit: George Metcalfe Archival Collection via Canadian War Museum).

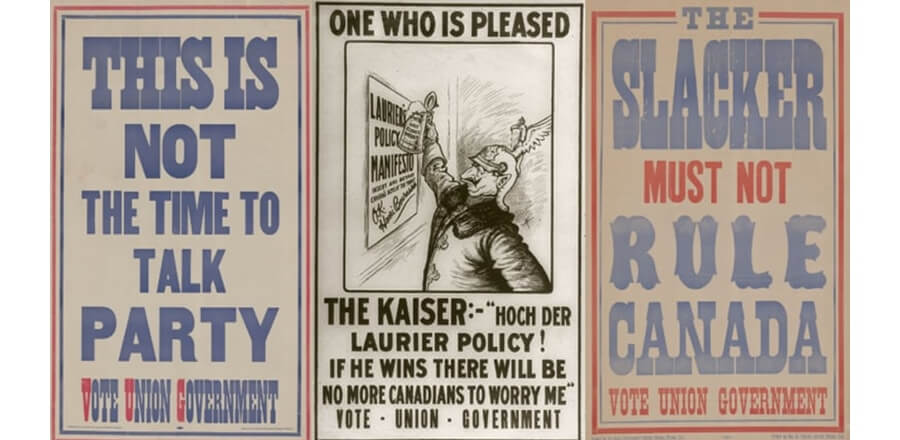

When Borden’s Military Service Act became law only months before the December vote anti-conscription demonstrations were triggered in Quebec and some conservatives began to deride French-Canadians, as well as others who disagreed, as the Kaiser’s henchmen. Throughout the autumn months of 1917 and into the spring of 1918 the issue of conscription continued to divide people across the country, in fact, a rift was widened between French and English-speaking Canada that still exists today.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

When Canada entered the war in 1914, Borden had assured voters that his government would not implement conscription. However, during a visit to the Western Front he changed his mind after talking to soldiers and amputees. He decided that the burden of war should be shared by all Canadians.

“. . . I cannot too strongly emphasize my belief that a great effort still lies before the Allied nations if we are going to win this war . . .”

– Prime Minister Robert Borden, Speech to the House of Commons on May 18, 1917

This speech followed his return from Britain and France. Before the end of that summer the Military Service Act would be passed into law. For the entire speech, click here.

Realizing that there would be resistance to his plan, Borden made every effort to ensure a win for his party on election day. One of his creations, the Wartime Elections Act, took the vote away from any immigrant having arrived in Canada since 1902 who had been born in an enemy country. In addition, any female relatives of Canadian soldiers and any military nurses were enfranchised (given the right to vote). These two changes were anticipated to skew the vote by decreasing the risk of anti-Union votes from recent immigrants in the former case, and by increasing the pro-Unionist votes by women who wanted to bring their loved-ones home from the battle (conscripts would be replacing them overseas) in the latter. Regarding the right to vote being given to some of the women, this was the first time that they were enfranchised federally, and this was fantastic, however, there were some ulterior motives in the reasoning behind the government’s decision. Regardless, it was a step forward for women and before the end of 1918, all women would be enfranchised (but this did not apply to aboriginals or Métis women, or men).

Another crafty move by P.M. Borden was the Military Voters Act. This law allowed the voting soldier or the government to apply the cast ballot to any Canadian riding nation-wide regardless of where each respective soldier was from. Borden’s government could now apply the votes wherever they were most needed.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

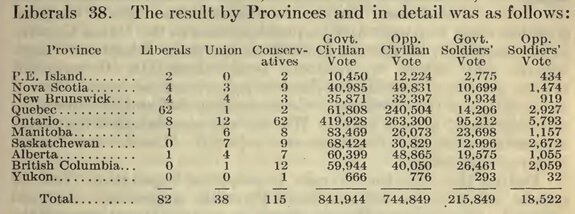

Once all of the votes were tabulated it was found that eighty percent of the soldiers on the front-lines voted in favour of Borden’s government (for conscription). Back in Canada, support for Borden’s government showed a 21 to 10 advantage in the Maritime provinces, a sweep of 41 to 1 in the western provinces, and in Ontario and Manitoba: the Unionists overwhelmed the Liberals 88 to 9. Even though the Liberals crushed Borden’s side in Quebec (62-3), the election was not at all close and conscription would occur in Canada. Months later when the first of 24,000 Canadian conscripts arrived in France, they were taunted by the veterans and given the cold shoulder.

Before retiring in 1920 and passing the leadership mantle to Arthur Meighen, Borden enacted some other notable laws (income tax in 1917, universal suffrage for women in 1918) and in 1919, he negotiated with Britain and the U.S. and won the right for Canada to participate as a “minor” power in the crafting of the Treaty of Versailles.

To learn more about the 1917 election, including the lead-up and the after-effects, visit the Canadian Encyclopedia.

For a microcosm that illustrates the interaction between the opposing sides (in Kitchener, ON), please review this TVO (18Dec2017) article: “A look at one of the ugliest federal election campaigns in Canadian history”.

Main photo: Various Unionist posters from the 1917 election (Credit: LAC via CBC).