Bomber Command

In times of war, one rule remains clear:

“He who controls the air, controls everything.”

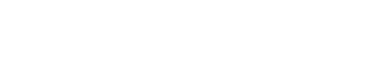

– General Giulio Douhet

Air superiority is often the decisive factor on the battlefield. As Nazi Germany swept through Europe in the early stages of the Second World War, its formidable air force, the Luftwaffe, played an important role in Germany’s rapid success.

With the rising tensions in Europe, the British government recognized the urgent need for an aerial bombing force and established the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command. Its primary mission was to conduct strategic bombing campaigns targeting key enemy infrastructures, thereby disrupting German wartime efforts.

“The Bomber Will Always Get Through”

Previously quoted Italian General Giulio Douhet, often called the “father of air power theory,” argued that strategic bombing would be a decisive factor in modern warfare – he predicted that defenders would be unable to prevent massive destruction from the air.

This fear was famously summed up by Stanley Baldwin, a British politician, who declared in his 1932 “A Fear for the Future” speech to the British House of Commons that “the bomber will always get through.” It was a stark warning that Britain’s air defences were vulnerable and could not guarantee protection from aerial bombing raids. An argument was made that a strong bomber force was essential to deter aggression. While Baldwin did not directly create the RAF Bomber Command, his words sparked a wider debate about Britain’s air defences.

Concerns about Britain’s aerial vulnerability increasingly grew as mainland Europe rapidly fell under Nazi control. Germany’s Blitzkrieg campaigns relied on swift and coordinated assaults combining air power, armour, and infantry, which proved to be dangerously successful, and with the fall of France on June 22, 1940, Britain was left isolated and vulnerable. The looming threat of a German invasion cast a long shadow over Britain, setting the stage for the Battle of Britain, a pivotal air campaign in which the British fought to defend their homeland against the German Luftwaffe.

A German Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 bomber flying over Wapping and the Isle of Dogs in the East End of London, September 7, 1940. (Credit: Wikipedia)

Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command:

The Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command was established on July 14, 1936, and was tasked with conducting large-scale strategic bombing campaigns. However, in its early years, Bomber Command faced significant challenges related to limited resources, outdated aircraft, inadequate facilities, and disagreements among senior officials over strategy and fundamentals. These issues left the program unorganized and inefficient. As a result, Bomber Command operations initially suffered heavy losses and could barely achieve their strategic objectives.

The program relied on twin-engine aircrafts such as the Wellingtons, Whitleys, and Hampdens, which had limited range and payload capacity, and were susceptible to enemy fighters and anti-aircraft weapons. British air tactics were still underdeveloped and aircrews often faced harsh conditions. In response to the heavy losses during daylight raids, Bomber Command was forced to shift to night-time bombing missions, despite their inaccuracy.

The early years of the war were grim, and victory seemed distant. Britain was defending the British Isles with every available resource. German U-boats prowled the Atlantic, relentlessly targeting merchant convoys to sever supply lines and starve Britain into submission. While the Blitz inflicted widespread destruction and casualties on the continent, Britain was fighting a desperate war on multiple fronts, with its survival hanging in the balance.

It was not until 1941 that key advancements shifted Britain’s fortune in the war.

First, the introduction of the four-engine Short Stirling, in February 1941, marked a new generation of RAF bombers. The Short Sterling was the first-four engine bomber in the RAF’s fleet however, the aircraft quickly proved to be underwhelming due to its low service ceiling, limited range, and modest payload capacity. Its shortcomings led to a short frontline service life, especially with the introduction of the Handley Page Halifax in March 1941 and the Avro Lancaster in March 1942 (including the Mark X Lancaster variant, produced and used by Canada). By 1943, the Stirling was withdrawn from frontline duties and reassigned to secondary roles such as minelaying, electronic countermeasures, and supply drops. In contrast, the introduction of the Halifax and Lancaster bombers marked a turning point within Bomber Command and the war. With greater bombing loads, extended range, advanced avionics, and improved survivability, these aircraft elevated the RAF’s strategic bombing capabilities and helped shift the momentum of the air war in Britain’s favour.

Second, on February 23, 1942, Air Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris was appointed as the Commander-in-Chief of the RAF Bomber Command. Under Harris’s leadership, Bomber Command underwent a major transformation. He orchestrated the Thousand Bomber Raids, which were designed to overwhelm German defences and devastate cities through immense force and numbers to crush morale and cripple industrial production. He demonstrated his mandate with the mass-bombing of the German city of Cologne, which was considered to be a success at the time. Harris’s strategy of strategic bombing not only targeted military objectives but also civilian areas. Bomber Command carried out Harris’ strategy well into the last months of the war.

Artistic portrait of Air Marshall Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris. (Credit: William Timym. The National Archives of the United Kingdom via Wikipedia)

Although Arthur Harris steered Bomber Command out of turbulent times, he remains to be a controversial figure. His Thousand Bomber Raids and overall strategy drew significant criticism both during and after the war, beginning as early as 1945. The heavy civilian casualties and rate of destruction raised serious questions about the morality and effectiveness of his methods. Some argue that since he acted with the full support of the British government and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, he was without fault. It should also be noted that Harris was widely appreciated and admired by the men who served under him.

Later in 1942, a special unit known as the No.8 Group (The Pathfinders) was created to locate and mark targets for the main bomber force, significantly improving accuracy. This approach reduced the burden on bomber crews and increased the effectiveness of bomber raids.

One of the most famous operations carried out by the Bomber Command was Operation Chastise, better known as the “Dambuster Raid”. On the evening of May 16th, 1943, the No. 617 RAF squadron set out on a mission to destroy critical dams in Germany’s Ruhr Valley using innovative bouncing bombs designed to breach the structures and flood vital industrial regions. Canadians played a notable role in this high-risk mission: 29 of the 133-aircrew were from Canada, highlighting our country’s important contribution to even the most challenging and innovative Allied operations.

To see what a typical day would be for Bomber Command crews, click here.

Canadian Contribution:

Canadians greatly contributed to Bomber Command with nearly one-third of Bomber Command personnel were Canadian. The most notable contribution was the No.6 Group, a dedicated RCAF formation within Bomber Command. Additionally, the No. 405 “City of Vancouver” RCAF Squadron was selected to be a part of the No.8 Group “The Pathfinders”, where they served until the end of the war.

Canadians also supplied many trained pilots through the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, which trained and educated pilots, from various nationalities (mostly from the Commonwealth), across training facilities across Canada. Approximately 131, 553 pilots graduated from this program.

Women in Action:

Women also played a vital role in Bomber Command’s operations. The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was created on June 28th, 1939, under the authority of King George VI. Members of the WAAF served on bases across Britain, performing roles ranging from cooking and communications to meteorology and aircraft maintenance. Women also served as civilian pilots in the Air Transport Auxiliary. The WAAF was initially met with skepticism, but the women of the WAAF soon earned respect and admiration for their determination, skill, and professionalism. Over a quarter of a million women served in the WAAF during the war, most between the ages of 18 to 40, and representing multiple nationalities within the Allied forces.

In Canada, Canadian women served in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAAF) both at home and abroad. They made significant contributions at the BCATP schools across Canada and the No.6 Group (RCAF) of the RAF Bomber Command.

Bomber Command’s legacy is both powerful and complex. Its relentless campaign forced Germany to divert vast resources to air defences and severely disrupted industrial production. However, the strategy of area bombing remains controversial for its devastating impact on civilian populations; many ethical questions have since been raised about the Allies’ actions in this regard. Yet, the courage and sacrifice of the aircrews, who faced some of the highest casualty rates of the war, stand as a reminder of their determination to help end the war. Today, Bomber Command is remembered not only for its role in the war but for the human cost paid by those who risked their lives.

Animated Map: Western Allies’ WW2 Air Missions

View the sobering animated map (below) that shows the intensifying air missions (aerial bombing by the Allies) throughout the Second World War.

A few things to note:

– the slow start and the flurry of activity in ’44 and ’45

– that Great Britain (RAF) was basically fighting the aerial war on its own during the war’s first few years

– the bombing of Sicily prior to Operation Husky (’43)

– the following progression north over the Italian peninsula

– the ever-tightening enclosure around central Germany

Animated Map Credit: FashionableNonsense (Reddit), likely an adaptation of this Imperial War Museum creation.

Main photo: Handley Page Hampden of No. 83 Squadron with crew, seated on a loaded bomb trolley at Scampton, Lincolnshire, 2 October 1940. (Credit: Imperial War Museums)

References:

“A Story of Discovery, Education and Remembrance.” n.d. International Bomber Command Centre. https://internationalbcc.co.uk/.

“About Bomber Command.” 2015. RAF Benevolent Fund. February 5, 2015. https://www.rafbf.org/bomber-command-memorial/about-bomber-command.

“Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris : Juno Beach Centre.” 2022. Junobeach.org. 2022. https://www.junobeach.org/canada-in-wwii/articles/air-marshal-sir-arthur-harris-2/.

Baldwin, Stanley. n.d. “A Fear for the Future .” https://missilethreat.csis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/A-Fear-for-the-Future.pdf.

“BBC – History – Historic Figures: Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris (1892 – 1984).” n.d. Www.bbc.co.uk. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/harris_arthur_bomber.shtml.

Bomber. 2014. “Project ’44.” Project ’44. 2014. https://www.project44.ca/bomber-command.

Ehlers, Dr Robert . n.d. “Bombers, ‘Butchers,’ and Britain’s Bête Noire: Reappraising RAF Bomber Command’s Role in World War II.” https://www.raf.mod.uk/what-we-do/centre-for-air-and-space-power-studies/aspr/apr-vol14-iss2-2-pdf/#:~:text=Critics%20have%20condemned%20Bomber%20Command,regime%20to%20sue%20for%20peace.

Imperial War Museum. 2018. “RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War.” Imperial War Museums. 2018. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/raf-bomber-command-during-the-second-world-war.

March, William. 2016. “RCAF (Women’s Division) | the Canadian Encyclopedia.” Www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. January 14, 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/rcaf-womens-division.

“Pathfinders.” 2025. Bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca. 2025. https://www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca/pathfind.html.

“RCAF Bomber Squadrons Overseas.” 2014. Juno Beach Centre. March 31, 2014. https://www.junobeach.org/canada-in-wwii/articles/rcaf-bomber-squadrons-overseas/.

“Short Stirling.” 2025. Bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca. 2025. https://www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca/aircraft_shortstirling.html.