The Battle of Batoche

When Manitoba became a province under the Manitoba Act of 1870, many Métis in the Red River Settlement were unable to maintain their lifeways given the influx of European settlers, and as a result, many Red River Métis relocated westward to Saskatchewan (SK). As the railway moved slowly towards the west coast and the settler population in Saskatchewan increased, the main food staple (i.e., bison) for Indigenous and Métis peoples dwindled, and Métis landholdings were disputed by the Canadian government.

In 1884, Métis at Batoche, SK, sent a delegation to the former leader of the Red River Resistance/Rebellion (LINK), Louis Riel, who was in exile in Montana. The delegates successfully convinced Riel to return and help them fight for their rights. Alongside Gabriel Dumont and other Métis leaders, Riel established the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan in Batoche. Recognizing Riel and Dumont as a significant political threat, the federal government sent Major General Frederick Middleton, Commander of the Canadian Militia, to Winnipeg to suppress what they saw as a rebellion. Hence the origination of the moniker North-West Rebellion, a name that refers to a sequence of events which today is more commonly referred to as the North-West Resistance.

The Battle of Batoche

The final and most significant battle of the North-West Resistance was the Battle of Batoche – it was fought from May 9th to 12th, 1885, between Riel’s Métis fighters and Middleton’s militia forces. Middleton, having met fierce Métis resistance during previous clashes at Duck Lake, Fish Creek, and Cut Knife Hill, intended to carefully encircle Batoche. As his main ground contingent advanced directly to Batoche against the Métis’ defenses, Middleton hoped that the steam-powered paddle wheeler Northcote, packed with his men and approaching Batoche by sailing down the South Saskatchewan River, would escape the defenders and land at the rear of town. Northcote, however, arrived ahead of schedule on May 9th before the Métis fighters were distracted. General Gabriel Dumont noticed the vessel, raised a ferry cable above the river and severely damaged Northcote’s steamer stacks. Having lost power, the vessel drifted downstream, and Middleton’s strategic encirclement failed.

Soldiers Sleeping Behind Fortified Walls at Batoche, May 1885. (Credit: Prince Albert Historical Society).

Despite the failure of the Northcote to arrive at Batoche with reinforcements, Middleton and his men continued with their advance on the town on May 9th. Although heavily supported by fire from Gatling guns, Middleton’s troops were fiercely repelled by Métis fighters. Both sides held their initial positions, retiring in the evening to sleep behind improvised barricades and fortifications. During the following two days, Middleton attempted conservative advances on Batoche by shelling the town; little on-the-ground progress was made but the Commander realized the Métis lacked the firepower to oppose a flanking attack from two sides. By the end of the day of the 11th, many Métis defenders had been killed, wounded, or scattered, and most were running low on ammunition. The Canadian militia forces were confident a flanking attack would allow them to capture the town.

The morning of the 12th had not gone according to Middleton’s plan: The Commander had arranged for two flanking columns to attack Batoche, and one, led by Colonel Bowen van Straubenzee, failed to attack because they did not hear the other column’s signal (i.e., their gunfire). After the failure of the planned attack and exasperated by Middleton’s abundance of caution in the preceding days, Canadian troops rushed directly toward the Métis rifle pits, firing at will. Métis fighters fought bravely but were overpowered by Straubenzee’s vast numbers of men and ammunition. Straubenzee and his troops charged into Batoche that day, drove the Métis from the town and thus ended the North-West Resistance.

The Métis leader, Louis Riel, was captured and hanged for treason on the 16th of November 1885, and Gabriel Dumont fled to exile in the U.S. much like Riel had after the 1869 Red River Rebellion. The battle resulted in significant casualties, with the Canadian militia reporting 8 dead and 46 wounded. There were 16 deaths and between 20 and 30 wounded on the Métis side.

Batoche, where the Métis Provisional Government was formed and the battle partially took place, has been declared a national historic site. The Battle of Batoche was a turning point in Canadian history: it marked the end of Indigenous resistance to Canadian expansion into the West, it highlighted the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights and self-determination in Canada, and it is remembered as a symbol of Métis resistance and resilience.

The Damaged S.S. Northcote After the Battle at Batoche, 1885. (Credit: Prince Albert Historical Society).

Additional Links/Information:

For more information on the Battle of Batoche, consider visiting the Batoche National Historic Site, and check out the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan’s photographs of Batoche.

- Batoche National Historic Site: https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/sk/batoche

- Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan’s photographs of Batoche: https://www.metismuseum.ca/browse/index.php/484

Photos:

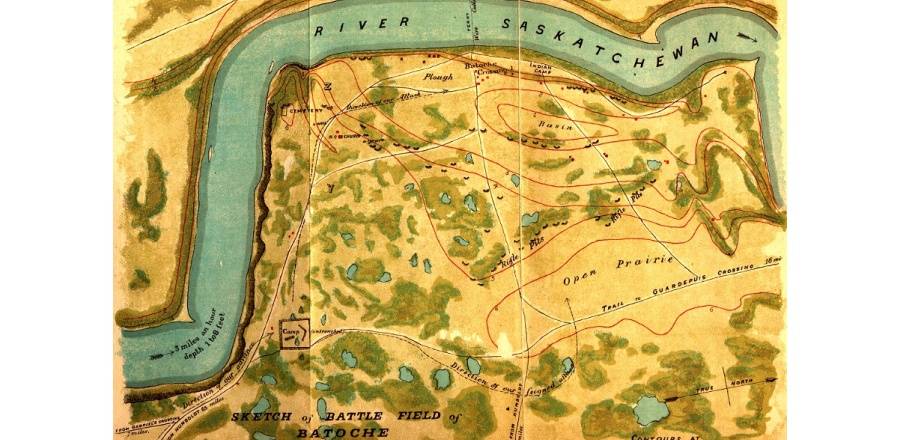

Main: A Map of the Battlefield in Batoche, Saskatchewan in 1885. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada, NLC-4369).

Sources:

Beal, Bob & Macleod, Rob. Prairie Fire: The 1885 North-West Rebellion. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1984.

Ens, Gerhard. From New Peoples to New Nations: Aspects of Metis History and Identity from the Eighteenth to Twenty-First Centuries. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Stewart, Sharon. Louis Riel: Firebrand. Dundurn: Dundurn Press, 2007.

Walter, Hildebrandt. The Battle of Batoche: British Small Warfare and the Entrenched Métis. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2012.