Battle of the Atlantic

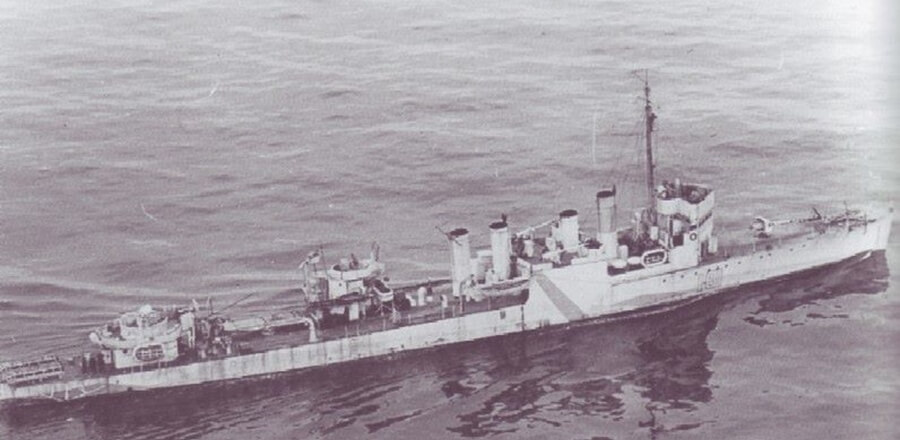

March, 1943: The technological cat-and-mouse race between the Royal Canadian Navy and the German Kriegsmarine’s U-boats finally shifted in favour of the former. Often viewed as the turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic, the tide’s turn actually began quite a bit earlier, with the late December sinking of U-356 by the destroyer HMCS St. Croix. Prior to this, the RCN experienced a “drought” that saw four months of no sinkings despite numerous wolfpacks faced by the convoys. This was odd, as the summer of 1942 saw numerous successes. What accounts for this drought?

Key to the success of St. Croix and later sinkings was the equipping on RCN vessels of the new Type 271 centimetric radar. Broadcasting at a much higher frequency than previous “metric” radars, the Kriegsmarine had yet to recognize this new capability.

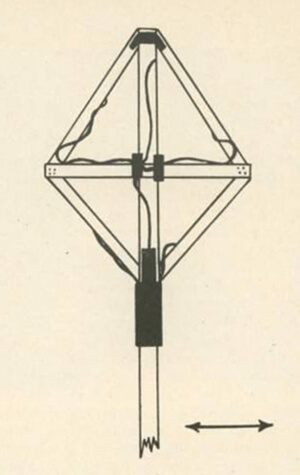

Diagram showing the simple FuMB 1 antenna made of wires wrapped around a wooden cross (Credit: uboataces.com).

The reason why, Rob Fisher argues, the U-boats had been able to attack Allied convoys with near-impunity during the autumn of 1942 was that the U-boats had been equipped with a simple radar detector called the Funkmessbeobachtung 1, or FuMB 1. The FuMB 1 was able to warn U-boat officers when a radar was operating in the 1.25 and 2.5 metre wavelength range – the range used by RCN escorts’ early SW1C and SW2C radars. A skilled user could even employ the FuMB 1 as a rudimentary passive radar, allowing him to determine the rough range and direction of the enemy’s radar.

The FuMB 1, despite numerous reliability issues, posed such a threat to convoys that some RCN escorts even had to turn off their radars to avoid being detected. It is crucial to remember that the FuMB could detect a radar signal at roughly twice the range that the original radar could detect a return due to the energy degradation of the signal.

The Type 271 that defeated it, its enclosure giving a distinctive lantern-like appearance (Credit: HMCS Sackville/Jerry Proc).

It was eventually realized by the Allies that the FuMB 1 could only detect signals in the above-mentioned wavelength range. The new Type 271, on the other hand, operated at 9.7 centimetres – well outside the FuMB 1’s detection capabilities. Thus, escorts equipped with the Type 271, like HMCS St. Croix, were able to approach U-boats using their radar without warning the latter away.

As a result, the RCN saw a “boom”, much like the summer of 1942, in their ability to prosecute U-boats from late December to March. After that, however, the “bust” returned, with very few sinkings once more. This time, though, it was not because the RCN escorts lacked the capability, but rather because operational changes reduced the chances that they would come into contact with marauding U-boats.

(Credit: this article has been condensed from Rob Fisher’s article on uboat.net)

Main photo: HMCS St. Croix in early 1942 with the old SW1C radar atop her mast (Credit: uboat.net).